The recent horrific acts of murder and terror in Paris, Beirut, Nigeria and Mali have reminded us that we still live in a world inhabited by violence, hate and evil.

These recent and almost simultaneous upheavals of violence and hate have shaken the foundation of our faiths, our trust in the moral order of the world, and our confidence in the basic goodness of humanity.

As we try to find a semblance of meaning, fear is covering many places like thunderclouds.

In the United States, as this phenomenon takes place and is inevitably mixed into the quest for power during an election year, the public discourse that consumes all the news broadcasts throws into bold relief the deep ideological fissures in our culture.

As a pastor and student of culture and society, I cannot but look at life and the world through theological eyes.

And what I see through those lenses during these days of grave social disruption concerns me very much as to how the voice of the church is being heard – or not heard.

Amid the din of absolutizing public conversations about fear, and the deluge of rhetoric that exploits that fear for personal gain, it is no wonder that it is also a time of great moral confusion for many of us.

Why are Christians disagreeing over an issue that the biblical texts address when they are reading the same Bible?

Or, for that matter, why are Muslims disagreeing over an issue that Koranic texts address when they are reading the same Koran?

Why are politicians disagreeing over an issue that the U.S. Constitution addresses when they are reading the same Constitution?

To think that these binary understandings of the world and morality can be resolved by simple argumentation – or impugning, invalidating and demonizing those who disagree with us – misses the critical role that our ideological habitat plays in shaping the way we understand the world.

And so is it uncommon for readers of the same sacred text to disagree over its meaning? No.

More decisively, is it uncommon for readers of sacred texts to pick and choose certain passages to prove the rightness of one’s perspective while dismissing or glossing over other passages in the same sacred text? No.

Is it possible that we do so not in the quest for truth but, perhaps unwittingly, to justify one’s own ideological perspective? Yes.

So which way is it to “true north?” Our perspectives are inherently limited and provisional, but there is a center that holds everything together.

Jesus was explicit in saying that he did not come to change nary a “dot or tittle” in the Scripture. Rather, he came to “fulfill” it.

In John 5:33-40, Jesus affirms to the Pharisees that, indeed, the Scriptures speak about life. Then he introduces a radically new hermeneutic: “But you do not come to me that you may have life!”

Fear dislocates the equilibrium of our inner worlds and awakens the yet unredeemed spaces of our humanity.

In the chaos, we instinctively seek order, and in that desperation to restore order, the path of least resistance is to find someone on which to blame the “disorder.”

The recent acts of terror took place during the massive migration of Syrian refugees to the West, inflicted by murderers based in Syria.

It has become easy to stigmatize an entire race for the sins of a few amid the chaos. And being an election year, the business is brisk for the political peddlers of fear. The drums of war beat once again.

Pope Francis said recently, in his grief, that in a world that still wages war and refuses to seek the path of peace, the festivities of the “Christmas season” become a charade.

The Advent season is upon us – a sacred time for Christians as we enter into the spiritual discipline of preparing for the coming of the Prince of Peace.

Do our actions look like Jesus? Do our words sound like Jesus? Does our compassion look like Jesus? Does our love look like Jesus?

In a time of great disconnective energy, the proclamation of the gospel in Colossians 1:17 is muted – that in Jesus Christ everything holds together.

We must “unmute” this gospel voice by being peacemakers who are obligated to do what is good and just, to be aspirants for what is beautiful, to love mercy and to walk humbly before God.

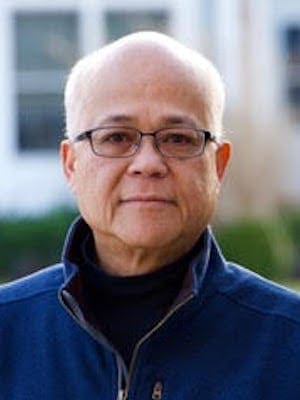

Elmo D. Familiaran is the associate regional pastor and area minister for the American Baptist Churches of New Jersey. A longer version of this column first appeared on the ABC-NJ website and is used with permission. You can follow him on Twitter @efamiliaran.

Elmo D. Familiaran is the associate regional pastor and area minister for the American Baptist Churches of New Jersey. A longer version of this column first appeared on the ABC-NJ website and is used with permission. You can follow him on Twitter @efamiliaran.

Elmo Familiaran is a pastor, writer and practitioner in the mission and purpose of the church in the world. Ordained in the American Baptist Churches, USA, he is a 39-year veteran in pastoral ministry, in ecumenical and cross cultural engagement, and executive leadership in both national and regional denominational settings.