The somber drama of Holy Week and the joyous celebration of Easter are past, with their annual re-engagement with the formative narrative of our tradition.

Now is a good time to reflect on the question: “What does it mean to be an “Easter people” from this point forward?

The question has been addressed often, especially since the term “Easter people” was introduced as the title of a collection of policy statements from a Bishops’ Conference in Liverpool, England, in 1980.

This conference met to discuss several then-controversial issues, which grew out of the Second Vatican council of the early ’60s.

If Easter is not just an event to be observed and celebrated, but a mystery to participate in and live into, what does this mean in concrete terms for our personal and corporate lives?

In recent days, three things have pointed in the direction of an answer to the question for me.

The first has been the reporting on the burning of three churches in Louisiana, allegedly at the hand of a man who has been charged with arson and hate crimes.

The stories of the churches’ multi-generational histories and central places in the lives of their communities have testified to their deeply meaningful significance. The sadness of their loss is deep.

Still, in spite of the deep emotion of their grief, respondents spoke of their will to rebuild and to continue to be families of faith in their communities.

Harry Richard, pastor of Greater Union Baptist Church in Opelousas, Louisiana, said, “They burned down a building. They didn’t burn down our spirit.”

Destruction, even at the hands of hate, didn’t get the last word here.

The second is the catastrophic fire last week at the Cathedral of Notre Dame, a treasured icon of medieval architecture, art, engineering and faith.

Thousands watched firsthand, and millions more from live broadcast, as an apparently accidental fire related to extensive renovation work destroyed much of the building and many of its valued artifacts.

The shock and grief were real and deeply felt, as people of many faiths watched together as this long-standing symbol of Christianity fell helplessly to the flames.

Yet, while the smoke was still rising from the embers, the talk turned to restore and rebuild – to bring together resources and people in a work of reconstruction that would not erase the loss, but move beyond it, adding a new dimension to the magnificence the cathedral had been.

Its restoration will be a tribute not only to its original designers and builders, but also to the resilience and teamwork of the human community who values what it has meant throughout history.

At this writing, nearly $1 billion of support has been pledged to the effort; and, in an interesting expansion of that spirit of generosity, over a million-dollar spike in the fund to support the Louisiana churches has occurred since the Notre Dame fire.

Also here, devastating loss does not seem to be having the last word.

The third pointer to an “Easter spirit” grows not from these two recent catastrophes but from the slow decay in the moral quality of our common national life.

The factors that contribute to this are so complex and pervasive, it is easy to despair that there is no way out of the condition in which we find ourselves.

But in the face of this moral and political paralysis, clear and articulate voices have stepped up to the microphone that see our problem for what it is and are offering constructive paths, even though challenging ones that will require significant readjustments, toward a healthier future.

These voices encourage the hope that efforts to exploit fear for short-term gain at the expense of the common good will not have the last word.

These three features of our recent and current experience have served as reminders of what it means to be an “Easter people.”

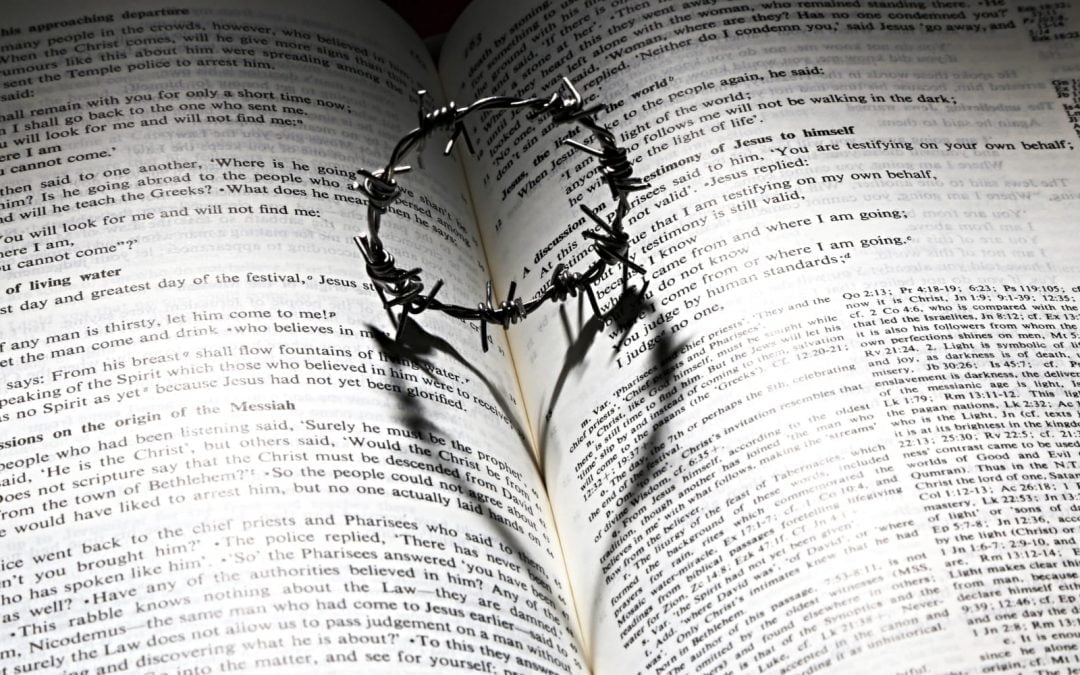

The journey of Holy Week looks toward the cross as the consequence of what the darker side of experience, intended and unintended, can produce. We are encouraged to see the presence of that dark side in ourselves and in the rest of life.

From the other direction, Easter offers a response to that darker side of the journey that prevents it from being the definitive word on what life is.

Looking back at the journey through the lens of Easter opens the creative power of human community to transcend and transform loss and death into new dimensions of life. It is, it seems, a way of seeing.

“Easter people” do not glibly or naively deny the awful reality of loss; however, as loss is experienced and passed through, it doesn’t get the last word.

At least that’s what I’m hearing from Louisiana, from Paris and in our national conversation.

Professor emeritus of religious studies at Mercer University, a member of Smoke Rise Baptist Church in Stone Mountain, Georgia, and the author of Keys for Everyday Theologians (Nurturing Faith Books, 2022).