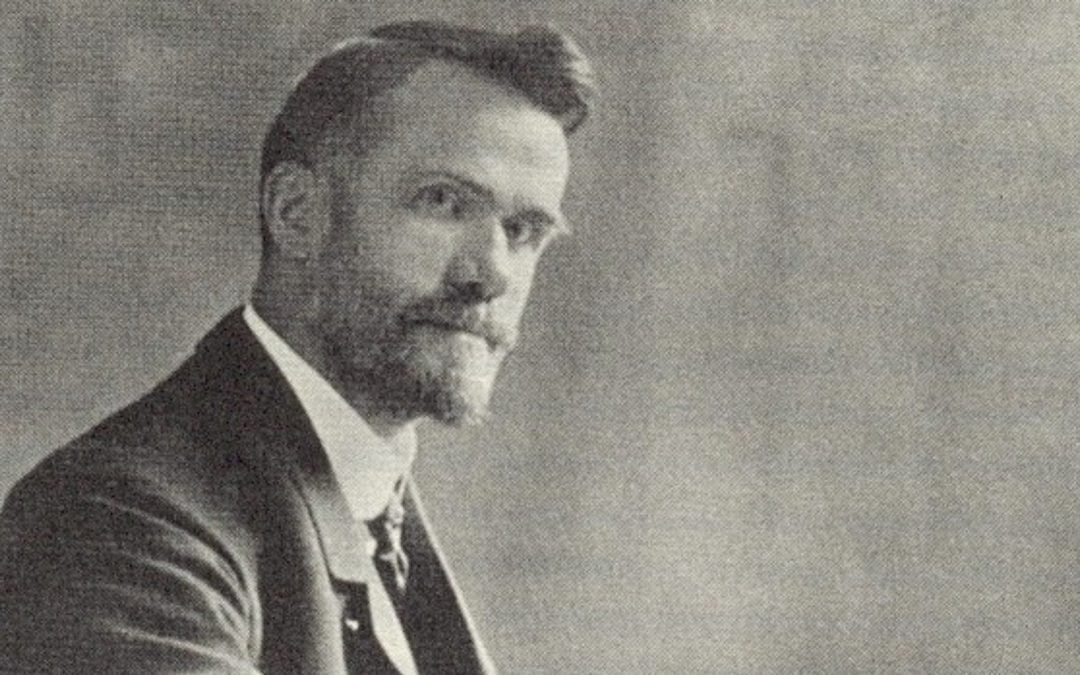

Walter Rauschenbusch was consumed with a passion for social justice.

Trained in Rochester seminary as a Baptist minister, he accepted a call in 1886 by the Second German Baptist Church in New York City, where he served for 11 years.

He was fluent in German as well as English and finished at the top of his class in both university and seminary.

But as he began his ministry among immigrants, he was distraught to learn that he had not been prepared to address the most urgent daily needs of his congregation.

New York City was filled with poor people whose only asset was their labor. Rauschenbusch wanted to help them with their pressing physical as well as spiritual needs.

He reported that the person who first gave him guidance in understanding the social and economic structure of the United States was Henry George, whose “Progress and Poverty” (1879) identified a troubling paradox: How could so much wealth be created and yet so many people be left in poverty?

His proposed remedy assumed the criteria of justice for all: The nation must look out for the welfare of all members of society.

This proposal fired Rauschenbusch’s imagination; he became a social activist for ways to improve New York City as well as a minister who preached the gospel.

Rauschenbusch did not view the gospel and social justice as two separate ways of life. Instead, his genius was that he incorporated the goal of social justice into Christianity.

In seminary, he learned that recent scholarship was convinced that Jesus’ central message focused on the Kingdom of God.

Rauschenbusch pondered the meaning of this concept. A kingdom is more than an individual. The model prayer does not declare “My Father,” but rather “Our Father.”

In his earliest sermons, Rauschenbusch proclaimed the gospel in terms of personal conversion experience, the familiar tradition of American revivalism.

However, in a sermon 18 months after his arrival in New York City, he proposed a larger two-fold understanding of the Kingdom of God: The individual is sinful and needs redemption; likewise, the structures of society promote injustices and are destructive to individuals; therefore, society also needs salvation.

The social gospel is the name given to this interpretation of Christianity.

Washington Gladden, Richard Ely and others had already articulated the concept of a social gospel. Rauschenbusch, however, would become its most compelling advocate.

Social salvation was not an optional addition to personal salvation; it was inherent in the gospel of Jesus. The church’s task is to address the need for salvation of society as well as the individual.

Henceforth, Rauschenbusch’s sermons and articles repeatedly addressed social issues.

In “Beneath the Glitter,” he pointed out that the vast wealth of the 1 percent was created from the deep suffering of the masses.

In another sermon, he condemned the ostentatious luxury and waste of people listed in the Social Register, the city’s 400 most prominent citizens.

A parishioner sent a blistering letter saying that Rauschenbusch was wrong to meddle in the lives of the wealthy. But he persisted.

In 1897, Rauschenbusch was called to Rochester Seminary to teach. Ten years later, he published “Christianity and the Social Crisis,” where he argued that the prophets denounced injustice in Israel’s society and called on the people to be fair in their treatment of each other. “This,” they said, “is what God requires.”

Rauschenbusch observed that this dimension of the biblical message had been obscured throughout most of church history.

The Industrial Revolution had exposed vast inequities and injustices. Rauschenbusch identified injustices perpetrated toward Native Americans, African-Americans and women.

However, the burning issue for him was the poverty of workers, which was caused by greed. The church must not abandon the workers.

This book resonated with many ministers, and the book made him famous. The permanence of Rauschenbusch’s influence was assured when the newly formed Federal Council of Churches adopted a social creed in 1908, clearly supporting Rauschenbusch’s goals for church and society.

In his 1912 publication, “Christianizing the Social Order,” Rauschenbusch devoted a chapter to “Justice” where he writes, “The simplest and most fundamental question needed in the moral relations of men is justice. We can gauge the ethical importance of justice by the sense of outrage with which we instinctively react against injustice.” He calls justice “the foundation of the social order.”

Rauschenbusch articulates the problem of injustice in terms of social class and economic inequity.

He explains that “theoretically we have no special privileges in America. Our country was ‘dedicated to the proposition that all men are created free and equal’.” But in reality, America has created a class of privilege based not on titles (as in Europe) but on wealth – larger fortunes generated in a single generation.

Few ministers were willing to criticize the American capitalist system as a major source of suffering and misery.

The wealthy paid meager wages, creating an unjust system of distribution of wealth. This is why Rauschenbusch supported a minimum wage, a 40-hour week and safer working conditions as well as city ownership of utilities and transportation.

In Rauschenbusch’s view, distributive justice was the major criteria for measuring the Christianizing of society.

Rauschenbusch thought America had made great economic strides forward but was still far behind in its moral responsibility.

Structures of economic injustice persist in America today. The imbalance of the economy is constantly in the news: poverty, debt, proposals for minimum wage, living wage and universal wage, health costs, the 1 percent and the rest of the population, failure to control payday lending and much more.

Rauschenbusch would sadly affirm that we are still a very un-Christian and unjust nation in our economic structures but would counsel us to work for the humane ideal of justice.

Editor’s note: This article is part of a series of articles for the World Day of Social Justice (Feb. 20). The previous article in the series is:

Why Social Justice, the Kingdom of God Go Hand in Hand by Colin Holtz