I often felt an inescapable tension between the “priestly” and “prophetic” dimensions of my calling as a pastor.

Priests help us with our relationship with God, while prophets call us to reflect on our relationship with God in our relationships with other people, with culture and with the systems and structures of society.

The primary locations of a priest are the sanctuary, the hospital, nursing homes, prisons, gravesides, counseling offices, living rooms, front porches and restaurants where conversations about life’s challenges unfold over a shared meal.

Priests listen more than they talk; and, when they do speak, they use the language of prayer and blessing.

The primary locations of a prophet are the streets, city hall, the county courthouse, community centers, media outlets, creative studios where art and music are made, and board rooms.

Prophets show up anywhere decisions are made or opinions are shaped that affect the common good.

Prophets spend a great deal of time in discernment and analysis; and, when they speak, they mainly question what is and describe what could and should be.

While the priest’s work is primarily within the church and the prophet’s focus is most often beyond it, we’re living in times when these distinctions are breaking down.

“Out there” – in public realms – a pastor will find many people, not necessarily connected with a church, who yearn for the listening, guiding and healing ministry of a priest.

They long to be heard, to have their spiritual needs taken seriously and to have someone help them honor the surprises of the sacred that appear in their experience.

“In here” – in the church – a pastor will find more and more reasons to raise prophetic questions about the relationship of faith to culture and to the principalities and powers.

I think that, in days ahead, church leaders will increasingly need to find wisdom, grace and courage to address the ways in which the culture tempts the church to baptize and affirm an order of things that is at odds with God’s kingdom of justice, mercy and peace.

Carlyle Marney cautioned pastors not to be “hand-tamed by the gentry” – not to allow the security afforded to priests to silence the prophetic impulse.

In my work as a pastor, I tried to heed that caution. It wasn’t easy. By temperament and training, I was more comfortable with the priestly role.

I know how difficult it is to distinguish partisan political issues from overarching issues of truthfulness, character and justice.

I was reluctant to speak painful truth to people I loved, and I was aware that congregations don’t welcome prophetic voices, especially from within.

Thankfully, though, I have an uneasy conscience. It wouldn’t let me completely default on my prophetic responsibilities.

At the very least, it caused me to worry about my failing to perceive, pray and speak as one who desired for “God’s kingdom to come and God’s will to be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10).

I worried that I was like the establishment authorities in Assisi during the time of St. Francis’ renewal movement, staying smugly and disapprovingly inside the cathedral, while he danced with hope and joy with the poor and the struggling.

I worried that I was like officials of the church in Germany and Rome who turned away from Martin Luther’s invitation to reform and sought to silence his voice.

I worried that I was like the moderate white ministers to whom Martin Luther King Jr. wrote from the Birmingham Jail – ministers who agreed with his goals but fearfully stood on the sidelines, cautiously, gradually but ineffectually nudging their churches away from prejudice and segregation.

Worries like these haunted me and haunt me still. Though they make me uncomfortable, I’m grateful for them.

As I wrestle, as we all do, with what faithfulness means in the face of complex and controversial issues, I need such worries to keep me from settling for the status quo.

They push me to use my voice to amplify the voice of Jesus who speaks in the cries of the oppressed, marginalized and victimized.

Poet William Stafford said, “Your job is to find out what the world is trying to be.”

That’s the job of a prophet: to find out what the world is trying to be – to discover and declare God’s dreams for the world.

Prophets trust, and invite others to trust, that God is bringing order out of chaos, peace out of conflict and hope out of despair.

They rest in the awareness, and invite others to rest in it, that God is lifting up love amid the ruins of fear and raising up life from the shadows of death. They challenge themselves, and they challenge others, to join God in that saving work.

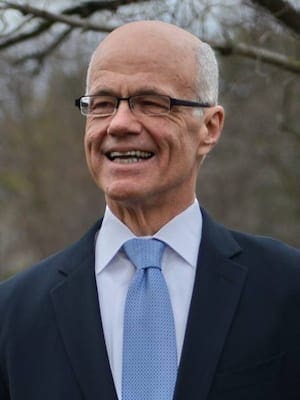

Guy Sayles is a consultant with the Center for Healthy Churches (CHC), an assistant professor of religion at Mars Hill University, an adjunct professor at Gardner-Webb Divinity School and a board member of the Baptist Center for Ethics. A version of this article first appeared on the CHC blog. It is used with permission. His writings can also be found on his website, From the Intersection.