I worked in a large hostel for 140 homeless people in the mid-1990s.

One resident (let’s call him Brian) had incredibly strong body odor. His lack of personal hygiene and reluctance to wash his clothes became a real issue.

It led to snide comments from other residents, and frustrations grew among those who shared the TV lounge or canteen area with him.

All the staff agreed that something should be done about the issue, but none of my colleagues was prepared to speak with Brian because they felt it would be too awkward and upsetting for him.

They said, “How would you like it if someone told you that you stink?”

I disagreed. I felt it was our responsibility to speak to him about it because it could lead to far more serious problems. In the end, I did it.

The conversation was difficult. Brian did get angry, embarrassed and upset. But he did take it on board and agreed to a simple plan to address the issue.

Even afterward, not all my colleagues agreed with my approach. They said things like “You are so harsh” and “I could never have said that to anyone.”

I thought about Brian when I read “Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion” by Paul Bloom.

To be critical of empathy is not easy. My wife (a counselor) got annoyed by just reading the title.

As Bloom puts it, “Being against empathy is like being against kittens – a view considered so outlandish that it can’t be serious.”

This is because “some people use empathy as referring to everything good, as a synonym for morality and kindness and compassion.”

So, to be clear, this is not a book against kindness or compassion.

Bloom says, “I am writing this book because I am for all those things. I want to make the world a better place. I’ve just come to believe that relying on empathy is the wrong way to do it.”

Rather, it is a critique of “coming to experience the world as you think someone else does.”

Bloom disagrees with the many who believe empathy is the most important thing we need to solve world problems: “The problems we face as a society and as individuals are rarely due to a lack of empathy. Actually, they are often due to too much of it.”

It is a thought-provoking thesis.

Does feeling the pain of others actually lead to good forms of help?

In the case of Brian, I felt my colleagues showed a form of empathy that did not lead to a compassionate response.

Their response was too affected by the thought of “How would I feel if someone said this to me?” rather than what was right in the circumstances we faced.

Bloom’s central point is that we need to use our heads more than our hearts and adopt a more rational approach to intervening positively in the world.

Emotional empathy gives too much sway to our feelings, to which our prejudices and inconsistencies easily cling.

“Those who are high in empathy can be too caught up in the suffering of other people,” he writes. “If you absorb the suffering of others, then you’re less able to help them in the long run because achieving long-term goals often requires inflicting short-term pain.”

A good illustration is parenting. Loving your children often means bearing the pain of the tantrum because you know, cognitively, that you are doing the right thing.

“Any good parent, for instance, often has to make a child do something, or stop doing something, in a way that causes the child immediate unhappiness but is better for him or her in the future: Do your homework, eat your vegetables, go to bed at a reasonable hour,” Bloom says. “Making children suffer temporarily for their own good is made possible by love, intelligence and compassion, but yet again, it can be impeded by empathy.”

Emotional empathy can leave us vulnerable to manipulation by those good at pulling our heart strings. Bloom gives examples of how this distorts our sense of proportionality and plays into our inherent bias.

People tend to help one person with a story that moves or connects with them, even when they could help many more with the same resources.

This is especially connected to my experiences of helping people with addictions and those begging.

Emotional empathy can lead us to prioritize what makes us feel good, rather than thinking clearly about what will really help.

Often, it is those with the best boundaries – rather than those overflowing with empathy – who provide the best forms of help. To be effective is to recognize manipulative behavior but continue to offer care and consistency.

As Bloom states, “Doing actual good, instead of doing what feels good, requires dealing with complex issues and being mindful of exploitation from competing, sometimes malicious and greedy interests. To do so, you need to step back and not fall into empathy traps. The conclusion is not one should not give, but rather that one should give intelligently, with an eye towards consequences.”

And this same dynamic is at work in managing staff. The best managers do not over identify with those they are responsible for but are able to rationally assess performance and be clear-headed enough to take required action.

I know that for myself, most of my poor decisions as a manager have been rooted in being too empathetic about those I manage, and not the other way around.

In the United Kingdom today, many people desperately need help. We need more than ever to think about what it means to be effective in our kindness and compassion.

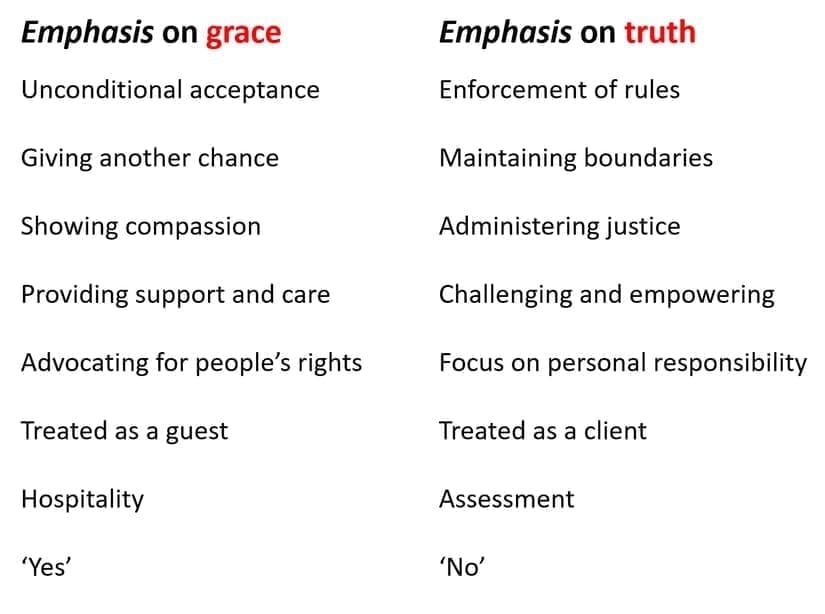

This is why I believe so much in the balance and fusion between grace and truth as shown in this chart:

Emotional empathy can lead us to simply focus on the “grace” side of the equation. And this tendency needs managing because positive change and transformation almost always involve both sides of this tension.

“Against Empathy” will not be everyone’s cup of tea. But I think it’s a helpful, provocative book that challenges us about how kind and compassionate our empathetic feelings really are.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared on Kuhrt’s blog, Grace + Truth. It is used with permission.

Jon Kuhrt is chief executive of West London Mission and a member of Streatham Baptist Church in South London.