Was Christian theology born in interfaith dialogue?

Recent expansions of interfaith discussions and relationships have not only broadened the boundaries of faith communities, they have also prompted reflections on the nature of theology itself.

“Theology” naturally brings to mind the abundance of doctrines that give expression to a given faith tradition.

For Christians, the complexity of those expressions has filled many a library shelf and overwhelmed many a student of theology.

Beginning with the simplicity of St. Anselm’s definition of theology as “faith seeking understanding,” the effort to do that has produced such comprehensive interpretations as Aquinas’ “Summa Theologica,” Calvin’s “Institutes of the Christian Religion,” Barth’s “Church Dogmatics” and Tillich’s “Systematic Theology,” among many others.

No wonder that pilgrims sometimes get lost in these forests of carefully refined theological precision.

Our first Christian theologian, at least the first from whom we have direct words that seek to interpret the Christian faith experience, offers an intriguing suggestion about the relationship between theology and interfaith dialogue.

Paul’s writing – and Luke’s later reports in Acts of his preaching and other encounters – point to a feature of his theological thought that is interesting in light of recent interfaith attention and activity.

Beginning in the relative simplicity (?) of an experience that transformed his faith perspective, Paul offers indications that his “conversion” was actually more an “inversion” of his understanding of faith from a reward-oriented concept to a gift-oriented one.

His numerous discussions of faith and works, grace and law as well as his understanding of the life of faith as the response of the whole person and not just a matter of good deeds and right beliefs, in many ways have been the transformative foundations of subsequent Christian theology.

Recall Luther’s study of Romans that played a significant role in his theological passion that contributed to the Reformation, and Karl Barth’s commentary on that same letter that influenced so much of 20th century Protestant theology.

I wonder if it is too far-fetched to suggest that Paul’s “inversion” that began what we know as Christian theology was actually a result of an interfaith encounter within himself.

We know from his own testimony that he was deeply rooted in the covenant faith of Israel (Galatians 1:13-14), and it is not surprising that he understood his “Christ encounter” in terms of that tradition and its categories.

His most comprehensive theological reflection in Romans goes to great lengths to relate Christ to the foundations of his faith tradition.

The conversation between what he had long believed and what he had personally experienced gave him a basis for his continued spiritual journey that neither would have provided alone.

And we know from other sources that Paul was most likely broadly educated in the culture of his time and place.

His study under the famous rabbi Gamaliel (Acts 22:3) – probably the ancient equivalent of attending a “liberal” seminary – would suggest that he was encouraged to refine his Jewish perspective by allowing it to be enriched by literature and history outside his particular tradition.

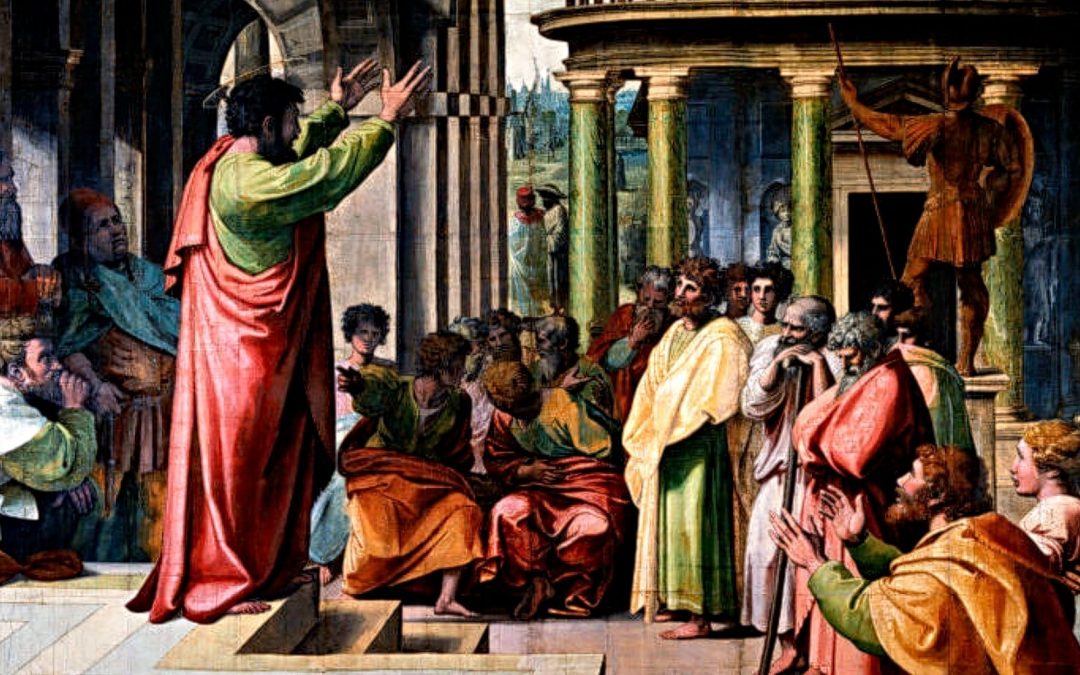

Two places in Acts that illustrate Paul’s ability to connect the faith he proclaimed with the frameworks of his audience are his sermon in Antioch (Acts 13:16-41) and his discussion in Athens (Acts 17:22-31).

In Antioch, his Christ experience is described clearly and comprehensively as in perfect continuity with the history and tradition of Israel.

His synagogue audience would have heard a profound affirmation of the sacredness of their own history being embraced by this “new” teaching.

In Athens, his address contains no reference to Abraham, Moses or the specific heritage of his covenant tradition, but instead quotes the poets and philosophers that his audience brought with them to the conversation.

What we see reflected in these two pieces of the Acts narrative is that Paul had both a depth of understanding of his own faith tradition and a breadth of knowledge and openness to insights from outside it.

Being a faithful steward of his Christ experience led him from being a defender of beliefs to being a pilgrim exploring the ways that God’s self-disclosure was taking place in an ongoing journey of faith.

The most explicit expression of this broadening understanding of his faith experience was his calling to be Christ’s ambassador the Gentiles (Galatians 1:16-17) – certainly a “barrier crossing” to his Jewish colleagues.

Once that barrier was crossed, there was no turning back to the exclusivism that had become part of his heritage.

Contemporary interfaith experiences often yield the testimony that not only do participants come to understand and appreciate the faith of others better than previous stereotypes allowed, but also they claim to find a deeper understanding of their own faith – growing more inclusive, more open to the diversity of God’s creative and redemptive work, more willing to embrace the theological humility that recognizes that all our concepts of God are partial “works in progress.”

Recent theological conversation seems to reflect this trend as well. A Christian theology born in interfaith dialogue might do well to continue to nourish itself in it.

Professor emeritus of religious studies at Mercer University, a member of Smoke Rise Baptist Church in Stone Mountain, Georgia, and the author of Keys for Everyday Theologians (Nurturing Faith Books, 2022).