While not exactly a household name, Fred T. Korematsu (born 100 years ago today, on Jan. 30, 1919) is becoming increasingly recognized as the civil rights hero he was.

Kakusaburo Korematsu emigrated from Japan to California in 1905. In 1914, a young woman named Kotsui Aoki came from Japan to become his wife. Five years later, their third son was born; they named him Toyosaburo.

Because all the Korematsu children were born in the U.S., they were American citizens.

When Toyosaburo started school, though, his teacher also wanted him to have an easier-to-pronounce American name – so she started calling him Fred, and the name stuck.

Fred went to the Castlemont Senior High School in Oakland and was a regular American high school student, running track and playing tennis. Things began to change for him, however, in the years shortly afterward.

As the war clouds began to grow darker in 1941, Fred and three of his good friends, all patriotic Americans, went to enlist in the U.S. military service.

His three white friends were given the necessary papers, but Fred was refused. Even before Pearl Harbor, there was strong prejudice in California against people with a Japanese face like Fred’s.

And, of course, things got worse after Dec. 7. On Feb. 20, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which resulted in about 117,000 ethnic Japanese people, the majority of whom were American citizens, being forced to live in internment camps.

Fred didn’t leave for the internment camp with his parents, though; he was going to try to “beat the system.” He failed.

On May 30, he was arrested and put in jail. Angry about being treated like a criminal, he vowed to fight his arrest.

Help unexpectedly came from a lawyer named Ernest Besig, who worked with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

Besig paid Fred’s bail and got him out of jail, but then Fred was forcefully taken away to the internment camp and became a prisoner there.

Fred had a strong sense of justice – and a strong sense that he and other Japanese-Americans were being treated unjustly.

He cooperated with the ACLU, which took his case all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. In December 1944, Fred learned with great sadness that Besig had lost his case before the Supreme Court.

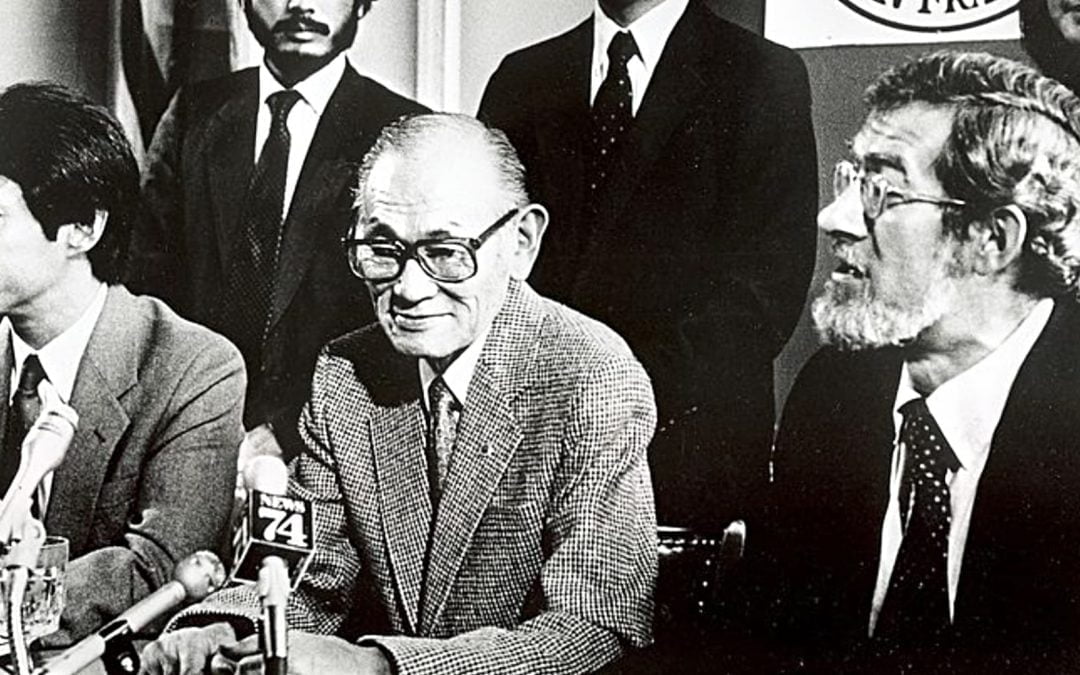

Forty years later, after Fred had married, raised a family and worked as a draftsman, he received a telephone call from Peter Irons, a law professor.

Irons said he had found new evidence related to Fred’s case and wanted to take it to the courts again. Fred agreed.

In 1983, Fred’s 1942 conviction was overturned. Five years later, Congress passed a law giving $20,000 in reparations to each surviving detainee in the Japanese internment camps.

Happily, for all those involved, in 1998 President Clinton awarded Korematsu the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor given in the U.S.

On Jan. 30, 2011, California celebrated the first Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution.

Now, Fred Korematsu Day is being celebrated “in perpetuity” by Hawaii, Virginia and Florida, in addition to California.

Most recently, in June 2018, the SCOTUS finally repudiated Korematsu v. United States; Chief Justice Roberts called that 1944 decision “morally repugnant.”

Unfortunately, however, in that decision the high court upheld President Trump’s Muslim ban. That was a painful irony for many people, including Karen Korematsu, Fred’s daughter.

Karen, who founded the Fred T. Korematsu Institute in 2009, lamented in a June 27, 2018, Washington Post article, “Racial profiling was wrong in 1942 and racial profiling is wrong in 2018. The Supreme Court traded one injustice for another 74 years later.”

On this special day honoring civil rights hero Fred Korematsu, let’s make sure that we realize – and that we help those within our circle of influence realize – that prejudicial attitudes or actions against racial and religious minorities are just as wrong now as they were in 1942.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared on Seat’s blog, A View from this Seat. It is used with permission.

A missionary to Japan from 1966-2004, he is both professor emeritus of Seinan Gakuin University and pastor emeritus of Fukuoka International Church.