Theological education is one pathway for women’s empowerment in the last 108 years of observing International Women’s Day.

I began an assessment of these trends yesterday, which draw primarily from the State of Clergywomen in the U.S., a report I compiled in 2018.

The aim of the report was to update statistics about ministry and theological education after a 20-year data gap.

The aim of International Women’s Day is a “global day celebrating the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women. The day also marks a call to action for accelerating gender parity.”

Theological education for women in the U.S. over the last 50 years has contributed to many positive changes for churches and the lives of women, as well as transformation in the church universal.

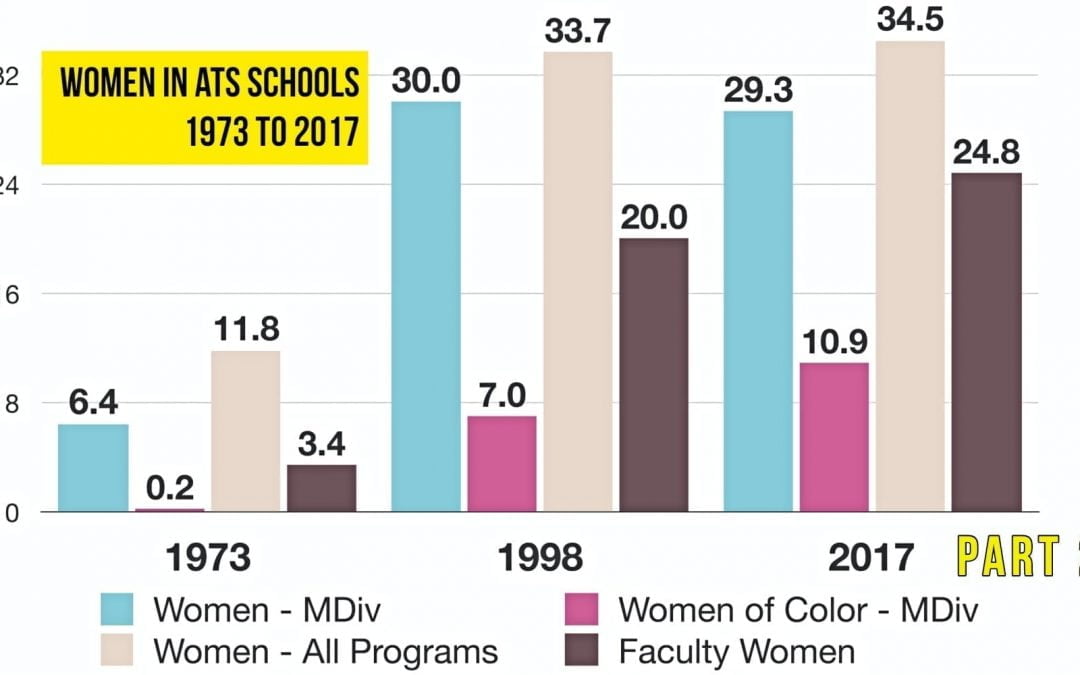

Theological education blossomed as a place for women to prepare for ministry in the decades between the early 1970s and the late 1990s.

Since that time, women’s participation has risen, peaked and then stagnated, following the recession of 2008.

By some measures, women are actually losing ground in the push to reach equity in theological schools.

The trends in theological education do not paint a very inspiring picture for women when you focus on the numbers alone.

With so many religious groups in the U.S. still unwilling to ordain or call women for leadership, I posed the question, somewhat tongue-in-cheek: “If churches won’t call women, why should seminaries educate them?”

Fortunately, the numbers are not the full story. And the movement of the Spirit cannot be contained by human institutions.

Here are six reasons we absolutely must keep educating women for ordained ministry:

- God is still calling women. And thus, seminaries need to continue educating them.

I’m teaching in Central Seminary’s Women’s Leadership Initiative, a master of divinity program, which focuses on helping women to be ready for the practice of ministry with their eyes wide open.

Special programs are not necessary for all theological schools. However, paying attention to the dynamics of gender, race, class, sexuality and other ways that society marginalizes people and teaching constructive responses are essential if we want the church to be a transformation agent and not simply a status quo agent in society.

- Women are not going away as church leaders.

The numbers are stagnant or down when it comes to theological education in many areas (faculty, deans and presidents, women in the master of divinity programs and so on). However, the numbers and percentages of women who are ordained and leading churches are dramatically up in the last 20 years. Thus, theological education remains crucial if for no other reason than to keep training women who are doing the work.

- Women will continue to lead the church even as the contours of ministry change.

Trends will probably continue to fluctuate based on many dramatic changes involving higher education, economics of theological education and ministry, as well as changing understandings of gender, sexuality and who can lead the church. None of those changes will undermine or diminish the need for creating theological education in multiple formats to prepare ministers to serve the church and serve the world.

- Women of color are just getting a foothold in professional ministry in the last 20 years.

One inspiring story comes from the African Methodist Episcopal Church, where women are leading in greater numbers.

As a denomination, they value an educated ministry and benefit greatly from women leading at every level of the church from licensed local pastor to bishop to seminary professor.

Many denominations centered in black, Hispanic and Asian ethnic groups remain at the early stages of making space for women to lead.

The number of women of color going to seminaries is rising. Now is absolutely no time to abandon an unwavering dedication to educate all women and particularly women of color for leading the church. The church needs their leadership.

- The church has done a lot of harm to women and children; theological education should be part of healing and preventing sexual abuse, harassment and discrimination.

Of course, this sounds idealistic in a world where #MeToo and #ChurchToo are not limited to churches. Perpetrators are still victimizing in many places, including seminaries.

However, the intellectual resources and access to time and space for making practical interventions remain one of the great contributions of theological education to the church as a whole.

Pressing for equity in theological education is good not only for the schools and students but also for the churches who receive well-trained ministers.

- Churches are ready for women’s leadership, and women are ready to lead.

Often, church pundits and male pastors like to say that the “churches are not ready for women” or conversely that “women are not ready to lead churches.”

My observations and research of the last quarter century help me conclude that churches are more ready than ever, and theological education needs to keep up the work of preparing women for ministry in the churches and beyond.

Editor’s note: This is the second of two columns. The first part appeared here. This article is part of a series for International Women’s Day (March 8). The previous articles in the series are:

Why You Need to Say the Other F Word in Church by Meredith Stone

Allowing Sexual Abuse Survivors to Find Their Voice by Pam Durso

She Matters: Providing Hope, Opportunity to Women Globally by Jennifer Lau

Examining Trends in Theological Education for Women – Part 1 by Eileen Campbell-Reed

Sisterhood Rocks by Laura Landgraf

Eileen Campbell-Reed teaches at Central Seminary, and she is codirector of the Learning Pastoral Imagination Project. In October 2018 she published the State of Clergywomen in the U.S., and she hosts Three Minute Ministry Mentor.