Captain Richard H. Pratt delivered a speech in 1892 addressing the education of Native Americans.

His words are haunting: “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him and save the man.”

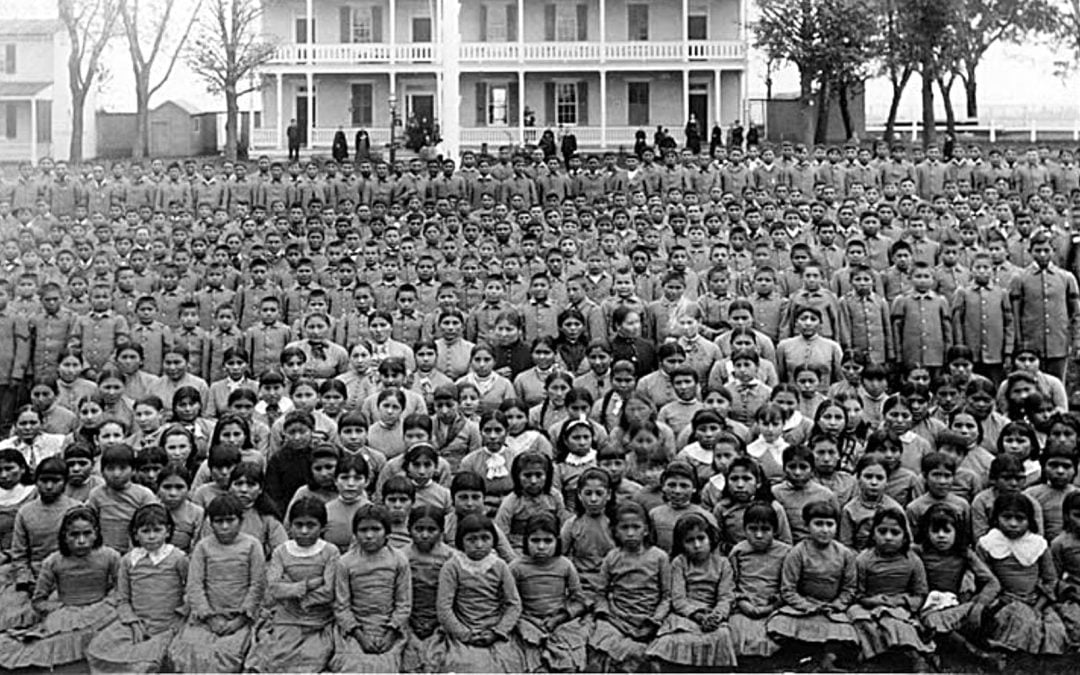

Pratt founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, more formerly known as the United States Indian Industrial School, beginning in 1879 at Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Pratt’s ideology was very complicated, as he believed “Indians” equal with European Americans, but “equal” only when assimilated into the European-American culture.

His ideology and school concept grew across the United States at the turn of the 20th century. Carlisle became the model for “Indian education,” with 26 schools emerging in 15 states.

While some argue the schools provided an excellent education for Native Americans, others portrayed them as nothing more than internment camps. Children were required to deny their customs and embrace a European-American culture.

The latter experience is the story of my great-grandmother, Eloise “Honey” Boudinot.

Honey and her sister, Ruby, were forced to reside and attend Chilocco Indian Agricultural School in north-central Oklahoma.

Uprooted from their homes and family in eastern Oklahoma, the young girls faced the worst possible experiences that resulted in lifelong trauma.

Upon arrival, the terrifying process of European-American assimilation began. The girls were forced to cut their long beautiful black hair – a sacred symbol for many Native Americans.

Their hair was fashioned into a “Christian” style, which meant the way white Protestant women wore their hair.

The girls were also told they could no longer speak Muscogee Creek, their native dialect.

If the girls were caught talking to one another using their native tongue, they faced warnings and eventually whippings.

For those in authority, English was the only appropriate language for a good Christian American.

Finally, according to Honey and Ruby, students were mandated to attend Sunday morning worship.

When the girls missed worship for anything other than being ill, the girls recalled receiving whippings for their absences.

Such forced worship and faith left a dark stain on my great-grandmother’s conscience for the rest of her life.

The type of Christian nationalism my great-grandmother encountered was both overtly and covertly implemented.

The dominant European-American Christians acted upon the belief of their superiority to other cultures, which they used as justification for enacting forced assimilation based on Christian evangelism and conversion.

Overt Christian nationalism merges Christianity with a political ideology to create a weapon seeking to dominate others.

Arguing for superior status based upon the false notion that the United States was founded as a Christian nation, overt Christian nationalism demands special recognition, consideration and accommodation.

When such efforts are successful, minority faiths and cultures are forced to take a backseat to those in power, thus securing their lower classification in society.

Covert Christian nationalism is much more subtle but just as dangerous. It uses language such as evangelism and conversion to argue the superiority of the dominant culture’s faith and politics.

This mode of Christian nationalism does not separate church and state but instead fuses them.

In other words, when individuals convert to this expression of Christianity, they are embracing both Jesus and a political ideology.

Within this misguided concept, a third element is added to the Great Commandment: “love God, love others and love the party.”

This idea is dangerous because it suggests a person cannot be a good Christian apart from the “accepted” political ideology.

When Jesus encountered the Samaritan woman at the well, he did not attempt to convert her (John 4:1-30).

The Samaritan culture was different from Jewish culture. Many Jews detested the Samaritans, even calling them dogs and half-breeds.

However, Jesus rejected Jewish nationalism that sought to divide. Jesus saw the woman as a human made in the image of God.

Listen to his answer when she asked about the right place to worship God. “Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem. But the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship him.”

Christian nationalism seeks to divide God’s children, raising an elected segment over that of others.

It also pushes the notion that one of the gospel’s main objectives is conformity, forcing converts to accept a faith and politic endorsed by those with authority, which in most cases are white males.

For the sake of my family’s history and the reality that Christian nationalism perverts and distorts the gospel of Jesus, I was one of the first signatories to the statement at ChristiansAgainstChristianNationalism.org decrying Christian nationalism.

I hope you and your friends will sign the statement along with me and others.

Editor’s note: EthicsDaily.com is running a series this week focused on Christians opposing Christian nationalism. It is published in conjunction with the launch of a BJC-led initiative ChristiansAgainstChristianNationalism.org. The articles in the series that have been published to date are:

U.S. Christians Speak Out Against Christian Nationalism | EthicsDaily.com staff

Threat of Christian Nationalism Has Reached High Tide | Amanda Tyler

Freedom Fighters: Baptist Defenders of Religious Liberty | Pam Durso

Your Fight Song Against Christian Nationalism: I Won’t Back Down | Brian Kaylor

Why Christian Nationalism Cannot Tolerate Crucified King | Jakob Topper

Can Theological Education Challenge Rising Nationalism? | Molly T. Marshall

Many Christians Don’t Acknowledge Their Christian Privilege | Michael Cheuk