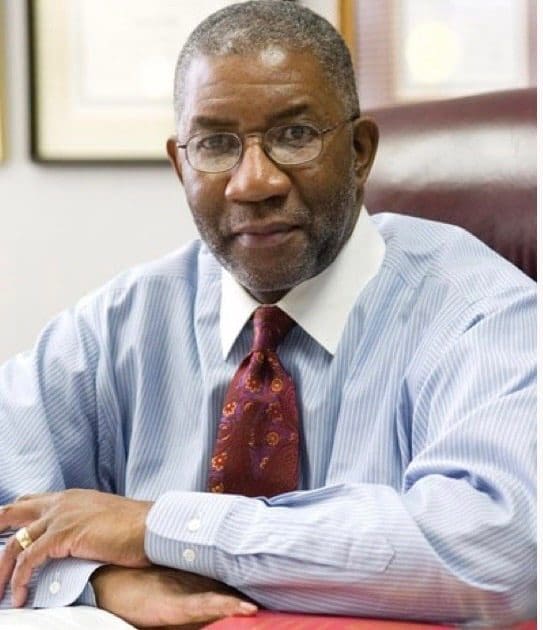

A sermon delivered by Wendell Griffen, Pastor, New Millennium Church, Little Rock, Ark., on September 26, 2010.

Jeremiah 32:1-15

Imagine that your nation was under attack and your capitol was besieged by an invading army. You believe that your nation should surrender rather than attempt to fight the invaders. You even say so. So you are arrested and placed in prison on charges of treason because your comments appear to support the invaders rather than your nation. If the invaders win, you don’t know what your future will be. If your nation wins, your reputation is still ruined and you might be killed anyway. How much land would you buy?

Well, let’s add a few more facts. Imagine the same situation I mentioned. Now imagine that you somehow learn that a cousin is in debt and in danger of losing his family property. He visits you in prison, tells you about his trouble, and offers to sell his family property to you. He’s your cousin. He’s trying to keep the land in the family. You have no wife and no children who might inherit the land after you die. If the invaders take over, you don’t know whether they will respect property rights or establish different laws that disrespect land title. Would you buy the land from your cousin? If so, how much would you pay? And if you bought it, would you tell others that you bought the land and how much you paid for it? Why would you do such a thing?

This happened to Jeremiah somewhere around 588 B.C. The lesson we read from Jeremiah 32 is perhaps the most lengthy and detailed account of a business transaction in the Bible. Judah has been invaded by the Babylonian Army. Jerusalem, the capitol city, is under siege by King Nebuchadrezzar. King Zedekiah of Judah had Jeremiah arrested and imprisoned for preaching that the Babylonian invasion was God’s judgment on Judah for idolatry and that the nation should surrender to the invaders rather than fight. In prison, Jeremiah is visited by Hanamel, the son of his uncle Shallum. Hanamel is in debt and needs to sell his land. He offers it to Jeremiah. Under the Hebrew law of redemption, a near relative was obligated to redeem Hanamel out of the financial difficulty (see Leviticus 25:25-28).

At Jer. 32:9-15, we read that Jeremiah bought Hanamel’s field, paid for it, had the deed witnessed, and gave the original deed and a copy to his assistant, Baruch, who placed it in an earthen jar for safekeeping. And at verse 15 we learn why Jeremiah made this weird deal. For thus says the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel: Houses and fields and vineyards shall again be bought in this land. Jeremiah believed God’s promised future for his people and the land. Despite the Babylonian invasion, the threatened conquest of his people, the uncertainty surrounding the future of his society, nation, and even his own life, Jeremiah believed God. So, Jeremiah bought the land, paid for it, and had the deed recorded and publicized. Jeremiah put his money on a future promised by God.

Jeremiah’s experience shows that trusting God can be troublesome. Then we see that betting on God means betting on hope.

Trusting God can be troublesome. Many religious people seem to think that trusting God should somehow give them an exemption from trouble. The prosperity gospel notion that God guarantees physical health and financial well-being to people who follow him did not begin with Joel Osteen, Bishop Eddie Long, Creflo Dollar, or even Oral Roberts, Reverend Ike, Daddy Grace, or Father Divine. In every generation there have been preachers and rulers who believed that they were divinely entitled to thrive, prosper, rule, and conquer no matter what.

And in every generation, there have been Jeremiah kind of troublemakers. They are the people who get in trouble, lose their freedom, sacrifice their reputations, and even risk their lives because they would rather live according to God’s justice and truth than follow conventional wisdom.

- Gandhi trusted the justice and truth of God and challenged the British Empire in India. It cost him his freedom and life.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. trusted the justice and truth of God and challenged the imperialist, racist, materialist, and militarist mindset of American rulers and the systems they operate. Doing so cost him personal security and eventually his life.

- Mother Teresa trusted the justice and truth of God and confronted the world about our indifference concerning people living in abject poverty and disease.

- Jimmy Carter trusted the justice and truth of God and confronted the United States and the world about its narcissistic value system that wastes and pollutes natural resources, oppresses poor and minority people, and violates human rights. So-called “religious conservatives” helped vote him out of office.

Trusting God—betting on God so to speak—can be troublesome because “conventional wisdom” places ultimate trust in self-centered and self-focused power and pursuits rather than on the purposes and power of God. People like Jeremiah are “weird” because they place ultimate trust in God, not their self-centered and self-focused notions of power, pleasure, and prosperity.

Betting on God means betting on hope! People who live according to the grace, justice, and truth of God are often hard to figure out. They do love strangers like family, forgive enemies, stand up for people who can’t give them anything and against people who can help or hurt them, and do other strange stuff. Because they build their lives on God’s purposes and power, they don’t bow and scrape to the usual bosses and bullies in life. They see things others don’t see. They hear messages others miss. They know truth that others deny. They’re just weird.

In fact, Jeremiah was trying to explain to King Zedekiah why he bought Hanamel’s land. Beginning at Jeremiah 32:3, we read: Zedekiah had said, “Why do you prophesy and say: Thus says the LORD: ‘I am going to give this city into the hand of the king of Babylon, and he shall take it. King Zedekiah of Judah shall not escape out of the hands of the Chaldeans, but shall surely be given into the hands of the king of Babylon, …and he shall take Zedekiah to Babylon, and there he shall remain until I attend to him, says the LORD; though you fight against the Chaldeans, you shall not succeed?” Zedekiah was perplexed. If Jeremiah was preaching this and believed it, why did he buy Hanamel’s land? Jeremiah explained that God had revealed to him that Hanamel would offer the land. The land offer was confirmed when Hanamel showed up and made it.

But Hanamel’s offer also confirmed that something else—God’s promise to restore and repopulate Judah. Jeremiah trusted God’s word of judgment concerning Judah and the political future of Zedekiah, to be sure. And Jeremiah also trusted God’s promised hope for Judah. God’s purposes were bigger than Zedekiah, bigger than Nebuchadrezzar, bigger than Babylon, and bigger than any other self-made and directed kingdom. . Jeremiah bought Hanamel’s land because he was betting that God’s promise of hopeful restoration was as true as God’s promised judgment. Jeremiah put his money on God’s hope! Jeremiah demonstrated his confidence in God’s promise by investing in it, publicizing the investment, and trusting the deal for a future he believed God would deliver. He saw beyond the invasion, beyond Zedekiah’s exile, and even beyond Babylon and Nebuchadrezzar and bet on a hopeful future based on the power of God.

We are called to be people of hopeful faith. Yes, Jeremiah is known as the weeping prophet. Yes, his preaching and living was defined by sad situations. But Jeremiah also experienced a sense of God’s future that was hopeful. He bought Hanamel’s land as a statement of hopeful faith. This leads one to wonder what hopeful faith might look like for 21st Century followers of God.

- Hopeful faith might nurture us to convert some prisons into schools where people who have been condemned as criminals can be restored to full and productive citizenship. Hopeful faith would see them as being like Hanamel—needing someone to invest in them, rescue them, and believe in them beyond their current plight.

- Hopeful faith might lead our church to join other congregations and the public schools to teach struggling young people to become good parents, and struggling children to become good students, and struggling neighborhoods to become healthy places for them to live, grow, learn, and work.

- Hopeful faith might lead followers of Jesus to challenge the conventional wisdom that we don’t need to spend money on poor people, sick people, elderly people, and immigrant people. Hopeful faith might lead us to invest our time, energy, and money in creating systems that lift people instead of label them.

Followers of Jesus are called to live by hopeful faith in God’s purposes and promises. We are called to bet on God’s resurrection power even in the Calvary situations that surround us. So we love in hope. We work in hope. We challenge our time and the kingdoms of this world in hope.

When our Hanamel kinfolk and their situations present themselves, we put our time, energies, and money on the line, despite how weird we look in doing so. We’ll sacrifice for our Hanamel kinfolk troubled by crime betting that the purposes of God are bigger than prisons and slums. We will sacrifice for our Hanamel immigrant kinfolk—and they are our brothers and sisters before God—betting that the purposes of God are bigger than fear-mongering and hatefulness. We’ll sacrifice no matter what the kingdoms and kings of our time say, or whether they understand what we are doing. We’ll do it openly, publicly, and confidently.

We aren’t called to live this way merely to build our own kingdoms. God calls us to do it because we believe in life based on hope. We’ll do these and greater things for the Hanamel people and situations around us when we are betting on God. Wouldn’t you rather bet with Jeremiah on God than on Zedekiah or even Nebuchadrezzar? Then base your living, your loving, your outlook, and your relationships on God’s purposes, God’s power, and God’s hope. That’s betting on God.

Pastor at New Millennium Church in Little Rock, Arkansas, a retired state court trial judge, a trustee of the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, author of two books and three blogs, a consultant on cultural competency and inclusion, and a contributing correspondent at Good Faith Media.