When the wheels on the Boeing 767 touched down in Beirut, Lebanon, I had no idea what I was to encounter.

After a week experiencing an incredibly diverse and warm culture – and encountering the hospitality of such a gracious people – when my plane lifted me up over the Mediterranean Sea to take me home, I left with both heartache and hope for Beirut.

My heart broke for the social-political realities of our past and present, but the people I encountered mended that broken heart with hope for the possibility of a peaceful future.

Before I dive into my experiences in Beirut last week, let me provide you some background about my personal history and how I had been raised to think about the Palestinian plight and the Middle East as a whole.

I am a child of the 1970s and ’80s, filled with Western media reports about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Growing up in right-wing evangelical churches (Southern Baptist), my head was filled with the notion that Israel was God’s chosen people without exceptions.

Israelis could do nothing wrong, while the Palestinians were the enemies of God’s divine plan for Israeli occupation of the Holy Land and could do nothing right.

Yasser Arafat and the Palestinian Liberation Organization were cast as terrorists working against God’s people. If U.S. Christians and the government did not support Israel at all costs, then we would face divine retribution.

As an adult and student of both the Bible and history, I now realize the issues once presented with such simplicity in my childhood are much more complex and nuanced than anyone can imagine.

In addition, there are always two sides of a story and only the unwise refuses to listen to both.

I knew all of this about myself before I boarded a plane in Oklahoma City for my two-day journey.

Therefore, when I arrived in Beirut, I did so with an open mind looking forward to experiencing a new culture and listening to the part of the story I had never been told.

Imam Imad Enchassi is a Palestinian refugee with U.S. citizenship who was born in Lebanon.

His grandfather made his way to Beirut, along with thousands of others, after Israel took control of their homeland and declared itself a nation-state.

Imad’s father settled in Beirut, establishing a local shop in the camp that offered fresh produce and other daily needs to refugees.

In the refugee camps, the Enchassi family experienced bombings from Israel, civil war between Christians and Muslims, and local factions fighting in the streets.

Imad’s formative years were shaped by these conflicts, the dark forces of war and violence pressing in from all directions.

Thankfully, even amid this deep darkness, a seed of hope was being planted in his soul.

As a young child, Imad attended a private school established by Catholic nuns in the camps.

The head nun, Samiera Abou Rahma (translated as “Ms. Mercy”) filled the children with compassion, love, peace and hope.

Receiving a safe environment to learn, sweets for the pure fun of it and a merciful lap to sit in, the children learned that while religion was important, unconditional love transcended everything.

Imad’s experience with Ms. Mercy shone an important light into his little heart that helped battle against the deep darkness that attempted to overcome him later in life.

As an adolescent, Imad could have easily joined the Palestine resistance, but his family wanted him to remain in school, changing the world through education and living a peaceful life.

Unfortunately, that peaceful life would be challenged in 1982.

After the assassination of newly elected Lebanese President Bachir Gamayel (the Lebanese constitution requires the president to always be a Christian), the Israeli forces laid siege to the Palestinian camps where Imad and his family lived. It was wrongly assumed the PLO carried out the attack.

Careful not to break a ceasefire, Israeli forces did not attack the camps. However, they permitted the right-wing Phalange Party militants, comprised mostly of Maronite Christians, to enter the Muslim neighborhoods claiming they were there to rid the camp of terrorists.

A massacre transpired when militants began to butcher all they encountered. For two days in September 1982, hundreds of men, women and children were slaughtered.

Running for his life, Imad hid in a room off an alleyway. He recalled how terrifying those days were for him.

At any moment, he expected someone to burst through the door, pull him into the alley and kill him. No one ever came.

After two days, the sounds from outside grew quiet. Still unsure if the violence had quelled, Imad made the decision to leave his sanctuary in the alleyway.

When Imad walked out onto the streets, he immediately discovered the deathly results of hatred.

For the next two days, Imad helped collect dead bodies. Estimates suggest 700 to 3,000 Palestinians died, mostly women and children.

According to Imad, the number of people killed could never be truly identified because of the extent of the carnage; the bodies had been so brutally mangled and torn apart.

Mothers and fathers showed up at the collection site wanting to discover the fate of their children, but Imad said there was no way to do so because of dismemberment.

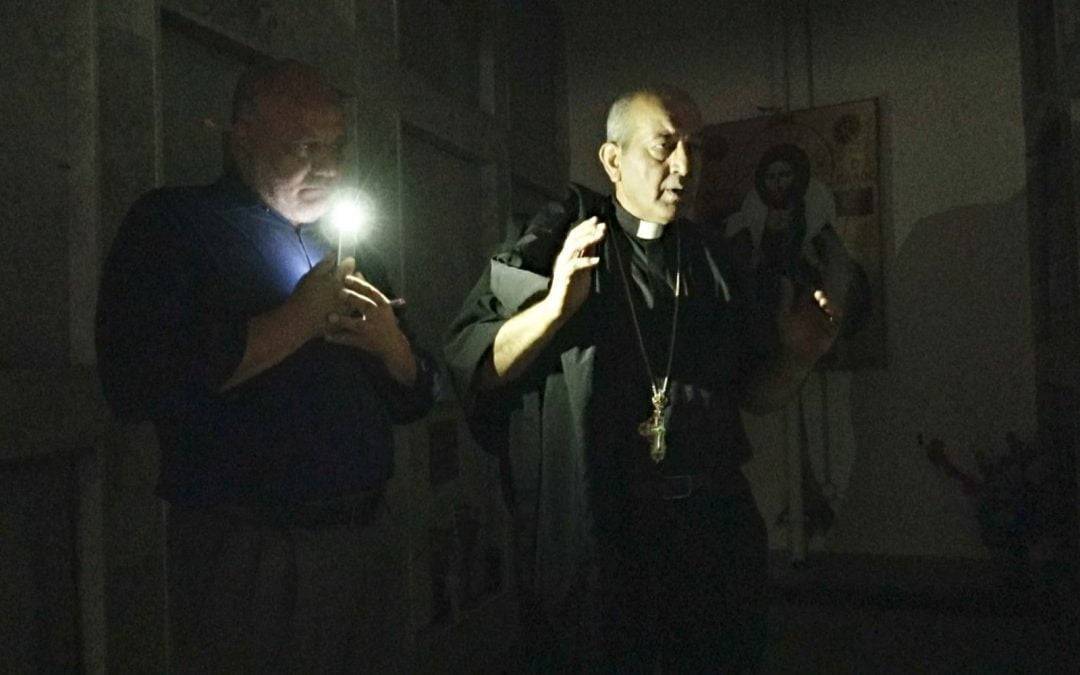

Walking onto the memorial grounds last week, Imad’s emotions took over as he openly wept at the enormous loss of innocent life.

With his responsibility of collecting the bodies concluded, Imad then returned home where his own family awaited the news of whether their youngest son and brother was alive or dead.

Enduring such a dark and evil event, it is hard to believe Imad did not allow hate to overcome his heart.

It would have been easy to give in to resenting and hating Christians, sending him down the dark path of vengeance.

However, for Imad, hate was too great a burden to bear. Instead, he recalled the life and witness of Samiera Abou Rahma, Ms. Mercy. Her compassion and love for all children offered Imad an alternative reality to embrace.

He would not walk down the dark path, but he would walk in light being a beacon of mercy and hope for others to witness.

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series. Part two is available here.