Thanksgiving’s origins are civic.

They have to do with the condition and conduct of the nation; and I believe that, for the United States, our giving thanks could – should – lead to repentance.

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the last Thursday of November to be a day for national thanksgiving.

Since the celebration of Thanksgiving by Massachusetts Puritans in 1621, there had been occasional official days for collective gratitude; after Lincoln’s proclamation, however, the nation has paused each year on a Thursday in late November to give thanks for its blessings.

Lincoln’s proclamation came amid the fierce fighting, human carnage and bloody despair of the Civil War.

With his characteristic eloquence, Lincoln asked that thanksgiving prayers include the commending to God’s “tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged.”

The president also called on the nation to approach the day of thanks with “humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience” and with fervent prayers that God would “heal the wounds of the nation.”

We’re not engaged in a civil war, but we are divided and not just into two camps, two parties or two ideologies (though it’s common for us to think in such reductionist binaries).

Politics isn’t simply Democrats over and against Republicans; it’s also Democrats in tension with other Democrats, and Republicans in conflict with fellow Republicans.

There aren’t merely two civic ideologies – conservative and liberal – but varieties of conservatism and liberalism as well as earnest attempts to be centrist or moderate.

Our culture wars are deeply damaging and seemingly unending. Pervasive violence, harsh incivility and paralyzing partisanship leave us fragmented and splintered.

Our society is loud with the noise of accusation, defensiveness and evasion. Some give powerful voice to their pain, while others defiantly dodge their responsibility for the hurts they have caused.

We don’t commonly use language like Lincoln’s to describe the things that are wrong with us.

We’re reluctant to speak of “national perverseness and disobedience,” and we’re unlikely to call for “humble penitence.” We should.

Our thankfulness would be more authentic if it included repentance – a turning in a new direction from what is wrong to what is right. Repentance for:

- The genocide of first nation’s people (Native Americans) whom many colonists savaged as savages to justify claiming their land for themselves.

- The enslavement of human beings upon whose labors the wealth of the nation was built and from which their descendants continue to be disproportionately excluded.

- The sexual harassment and abuse of women (and of some men) both at home and in the workplace.

- The granting of vast and unearned privileges to white men.

- The addiction to violence, one tragic example of which is that more Americans have been killed by privately owned firearms than in all the wars in U.S. history.

- The bombastic and boorish behavior of too many so-called leaders.

- The hyper-politicization of education and healthcare, leaving the young unprepared for their futures and the sick, especially the impoverished sick, without care.

- The excessive consumerism that seeks to fill a spiritual and emotional emptiness with “stuff” rather than with spirit and with meaning.

It seems disingenuous to me to say that we’re grateful for our blessings when we’re complicit in, or complacent about, the ways we leave people outside the abundance for which we give thanks. It’s like eating a Thanksgiving feast while starving people stare through the window at the bounty of our tables.

I’m troubled by the state of our disunion. This Thanksgiving, I’m asking what needs to change in and about me so that I can be a peacemaker, a reconciler and a bearer of God’s love.

I’m asking, in other words, about repentance.

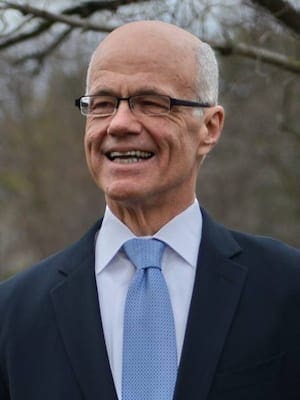

Guy Sayles is a consultant with the Center for Healthy Churches (CHC), an assistant professor of religion at Mars Hill University, an adjunct professor at Gardner-Webb Divinity School and a board member of the Baptist Center for Ethics. A version of this article first appeared on his website, From the Intersection, and is used with permission.