Last Monday was the somber 16th anniversary of the 9/11/2001 terror attacks: A plane went down in a Pennsylvania field, another plowed into the side of the Pentagon, and two became passenger-bearing bombs that brought down the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

While we remembered those violent events, we also held our collective breath as news came from places where Hurricane Irma was wreaking havoc: damaging winds, excessive rain, storm surges, flooded streets, destroyed property, displaced people and tragic deaths.

As in places ravaged just a week before by Hurricane Harvey, there is a long season of difficult recovery ahead. Rebuilding homes and businesses will be a steep challenge; refashioning hope will be steeper still.

Terrorism and hurricanes are just two of the threatening realities over which we have so little control.

Democracies that intend to safeguard civil liberties – freedoms of speech, religion, press and assembly – face significant limits on the means which they can legitimately use to keep their citizens safe.

Though we’re tempted to trade away freedom in exchange for security, it’s a deceptive and dehumanizing bargain we need to resist.

Besides, we’ve painfully learned that someone who is willing to sacrifice one’s own life for a cause can use a vehicle or a bomb strapped to the body to visit destruction and panic on people who’ve gathered in public places.

And, there’s almost nothing we can do about the weather (though I’m persuaded that human activity contributes to climate change and that the warming of the planet is a factor in the intensification of storms), we can build more carefully, and we can stop the building in places known to flood frequently or on seismic faults.

The hurricanes and tornadoes rage, however. Earthquakes shake foundations, and wildfires blaze. They batter and consume homes without stopping to ask about the race, socioeconomic status, gender, sexual orientation or age of the people who live in them.

We have so little control. In fact, we have even less than a little – at least less than we imagine we have when our lives are stable and conditions are calm.

Unexpectedly, though, a spouse gets a hard diagnosis, a friend has a wreck, an investment goes bust, a stroke strikes, the company closes its doors, a dictator develops a nuclear weapon that he aims at us and our allies, or our grown child tells us her marriage is ending.

In this out-of-control life, I try to remember the accumulated wisdom of many traditions: Though we cannot control what happens to us, we can control our response to what happens to us.

Victor Frankl, writing from his experience in Nazi prison camps, compellingly expressed that wisdom. “Everything can be taken from a [person] but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

He also said, “Between stimulus and response lies a space. In that space lies our freedom and power to choose a response. In our response lies our growth and our happiness.”

We get to choose how we will respond, and our choices will almost always be wiser and more life-affirming if we can lengthen the space between stimulus and response if we can mindfully pause to ponder and to pray before we act.

It’s possible – not easy, but possible – to respond to events beyond our control with love – love that seeks and sees us through pain, wherever the pain takes us, that sends us to rescue and to comfort others subjected to hurt, and that assures us that we aren’t ever, even when the worst things happen, alone.

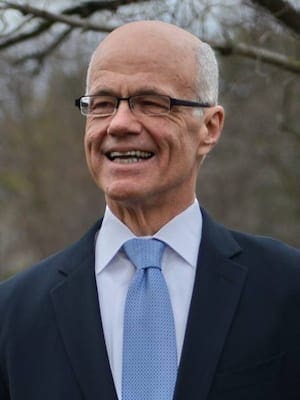

Guy Sayles is a consultant with the Center for Healthy Churches (CHC), an assistant professor of religion at Mars Hill University, an adjunct professor at Gardner-Webb Divinity School and a board member of the Baptist Center for Ethics. A version of this article first appeared on CHC’s blog and is used with permission. His writings also appear on his website, From the Intersection.