I’ve lived in our east Asheville, N.C., house longer than I have lived in any house in my entire life, including during my childhood. Before coming to Asheville, I lived in:

â— Huntington, W.Va.

â— Five different houses and communities in greater Atlanta

â— Statesboro, Ga.

â— Louisville, Ky.

â— Edwardsville, Ind.

â— LaGrange, Locust Grove, Montezuma and Griffin, Ga.

â— Metropolitan Washington, D.C.

â— San Antonio, Texas

â— St. Louis

It’s my version of Johnny Cash’s “I’ve Been Everywhere,” and every move I have made has been disorienting.

That disorientation was especially vivid the first time I moved out of the deep South, where:

â— Baptist churches held a near monopoly on religion

â— Sweetened iced tea was the house wine

â— Fried green tomatoes were a delicacy

â— Grits were as common at breakfast as coffee

â— Loyalty to a football team was a cause for which to be prepared to die

I discovered that there are places in this country where a Catholic church towers in every neighborhood but a Baptist church is hard to find; salsa is more common than ketchup; and you can shop for a Christmas tree in shorts, a T-shirt and flip-flops.

By contrast, I have lived in other places where people actually understand ice hockey.

Every move has involved a steep learning curve. You frequently find yourself driving with a map or directions close by as you seek to find doctors and a dentist, good but affordable restaurants, a reliable and honest mechanic, a dry cleaner, a barber, a bank, a bookstore and a racquetball court.

It takes a while to get your bearings.

One thing I’ve learned from moving is that a fresh start in a new place doesn’t necessarily result in a genuinely new beginning.

For instance, a move will not help if you have patterns of self-sabotage, a history of trouble dealing with authority and haven’t taken the time and gotten the help to figure out why you undermine your own success, act against your own self-interest and engineer conflict with your boss just like you did with your dad.

It won’t be long until the new job will be just like the old one because you took your old self with you to the new work.

A new house doesn’t automatically make a new home, either. Unless you deal with your own needs and wounds, you’ll be just as lonely, angry and clueless in the new house as you were in the house you left.

Changing places doesn’t always change us. It depends on whether or not we let new places, people, demands, opportunities, questions and ideas penetrate beneath the surface of our experience.

Transformation requires challenging how we think, feel and act. A lot of us resist rather than embrace such challenges. We defend ourselves against newness even when it confronts us. We live superficially and, therefore, meaninglessly.

That’s why we should pay more attention to the inward dimension of our faith journeys – a dimension we too often neglect

Former secretary-general of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjold, was right when he said: “The longest journey / Is the journey inward.” Faith is not mainly an external and geographical pilgrimage; it’s internal and biographical.

We journey with Jesus into the depths of our minds, hearts and spirits. We explore more and more of who we are and who we may become.

With Jesus at our sides giving us courage and strength we would not otherwise have, we take what Joseph Campbell once called “a hero’s journey.”

With Jesus, we fight dragons of temptation and defend ourselves against invasions of despair. We rescue the child who lives chained in a cave of old wounds, and we give him or her room to run and play again.

We claim the crown of blessing God gives to all of God’s beloved, and we join God in taking delight in, and caring for, the world. We uncover treasure buried in the mud of memory.

Dreams we barely allowed ourselves to dream wash over us like a breeze. Wonder overtakes us and awe overwhelms us as we discover the light of our true selves in the even brighter light of Jesus who is with us on the journey.

Because this inward journey involves confronting hard inner realities, many of us refuse to take it. We go numb, get stuck and stay stuck instead.

We opt for the wrong kind of contentment and comfort, shrinking back from the challenge of life and the invitation of God.

We refuse to keep company with holy restlessness and divine longing, committing the sin of failure to grow.

Faith means pressing forward, which, in this case, means journeying inward, confident that the journey leads to life as God means it to be.

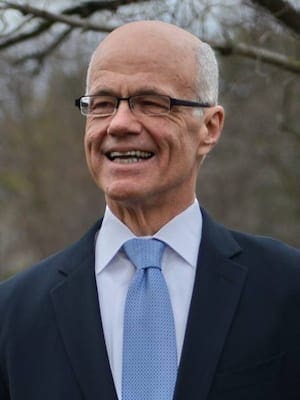

Guy Sayles is pastor of First Baptist Church of Asheville, N.C. A longer version of this column first appeared on his blog, From the Intersection, and is used with permission.