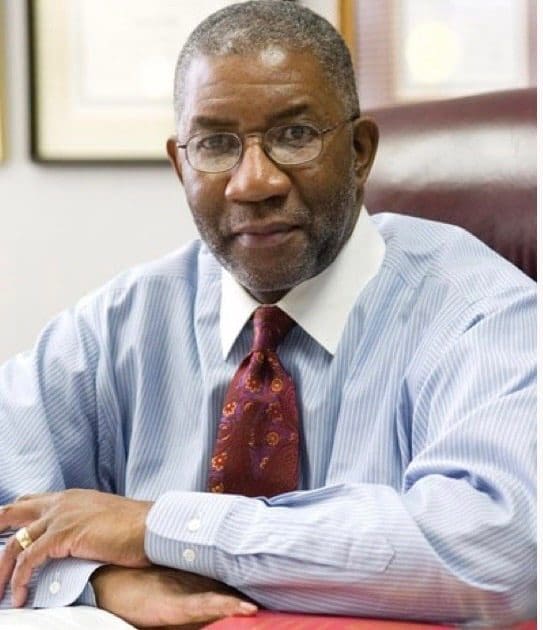

A sermon delivered by Wendell Griffen at Community Chapel at McAfee School of Theology, Atlanta, Ga., on November 15, 2011.

Matthew 22:15-22

15 Then the Pharisees went and plotted to entrap him in what he said. 16So they sent their disciples to him, along with the Herodians, saying, ‘Teacher, we know that you are sincere, and teach the way of God in accordance with truth, and show deference to no one; for you do not regard people with partiality. 17Tell us, then, what you think. Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?’ 18But Jesus, aware of their malice, said, ‘Why are you putting me to the test, you hypocrites? 19Show me the coin used for the tax.’ And they brought him a denarius. 20Then he said to them, ‘Whose head is this, and whose title?’ 21They answered, ‘The emperor’s.’ Then he said to them, ‘Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.’ 22When they heard this, they were amazed; and they left him and went away.

You are familiar with the term “loaded question.” A loaded question is a question with a false or questionable presupposition, and it is “loaded” with that presumption. The question “Have you stopped beating your wife?” first presupposes that you have a wife and that you have beaten your wife before asking whether you are beating your wife. If you are unmarried, or have never beaten your wife, then the question is loaded.

Since this example is a yes/no question, there are only the following two direct answers:

- “Yes, I have stopped beating my wife”, which entails “I was beating my wife.”

- “No, I haven’t stopped beating my wife”, which entails “I am still beating my wife.”

Thus, either direct answer entails that you have beaten your wife, which is, therefore, a presupposition of the question. A loaded question is one you can’t answer directly without implying a falsehood or a statement that you deny. The proper response is not to answer the loaded question directly, but to either refuse to answer or to reject the question. Thus, one avoids being tricked into affirming something as true that isn’t believed to be true.

“Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” was a loaded question.

It was politically loaded. Judea and Galilee was occupied territory. The indigenous population was reduced from a sovereign nation and had been turned into a troublesome colony of a foreign government. Palestine was part of the Roman Empire, but the indigenous population despised the very idea of being subjects of a foreign power in their own land. Everything associated with the Empire was a reminder about being over-powered. A direct answer to the question about paying taxes to the emperor would have conveyed the idea that Jesus accepted the imperial claims of Rome and all the indignities the population of Judea and Galilee associated with it.

The question about paying taxes to the emperor was also theologically loaded. For the Jewish population of Judea and Galilee the term “Lord” was synonymous with God. But to the Romans, the emperor (Caesar) claimed absolute power. The Romans declared that “Caesar is Lord.”

The question posed to Jesus invited him to either encourage people to pay taxes to a foreign ruler who made blasphemous claims or publicly oppose the political legitimacy of the Roman Empire in Palestine.

Jesus knew that the question about paying taxes to the emperor was a trap. Instead of answering the loaded question, he challenged his interrogators about the scope and thrust of power. He asked them to show him the coin used for paying the tax. The money used for the tax was the Roman denarius. Jesus literally told his questioners: “Leave me alone. You’re using Caesar’s money for everything else. Pay Caesar’s tax bill. You also have an obligation to God. Fulfill it.”

Jesus is talking about power. What is he telling us?

Don’t forget the difference between God and the government. The Romans weren’t the first or the last people who claimed that their political leaders demanded ultimate allegiance. Every period of history has involved claims by human rulers who made similar claims. Yet from the Exodus confrontation between the Egyptian Pharoah onward, the Bible reminds us that God doesn’t take second place to any government. No matter what title they claim, human rulers never constitute ultimate authority. No matter what system of government people embrace, the government doesn’t deserve ultimate allegiance.

And in shining the bright light about that difference between God and government, Jesus addressed the moral and ethical challenge that always surrounds how people of faith relate to government. No matter who runs the government or what form of government is imposed, people of faith have a divine duty to hold rulers and governmental systems accountable to the divine standard of love. Because we know the difference between God and government, people of faith have a non-negotiable and non-delegable duty from God to hold rulers accountable for how people are treated in a society.

- Because we know the difference between God and government, we have a duty to hold rulers accountable for the condition of vulnerable people.

- We have a duty to hold rulers accountable for hungry children and families.

- We have a duty to hold rulers accountable for homelessness and poverty.

- We have a duty to hold rulers accountable for military adventures that leave men and women maimed and scarred, that turn children into temporary or permanent orphans, that infect other people enduring bitterness, and that are used to enrich opportunistic merchants who have turned war-making into a commodity.

- We have a duty to hold rulers accountable for inhospitality toward strangers. How can people who claim to love God with their whole being intelligently ignore, let alone endorse, strangers being treated as criminals? How can people who claim to be nurtured in the faith of the Exodus support oppressing immigrant workers? How can the followers of Jesus, who as an infant was an undocumented immigrant in Egypt, refuse to hold rulers accountable for proposing and supporting laws that make it a crime to help an immigrant find a job, or that deny public assistance to immigrants?

- Because we know the difference between God and government, people of faith have a duty from God to confront any ruler and government that protects privilege and ignores suffering.

People of faith should learn from what Jesus said in responding to the loaded question about paying taxes to the Roman Emperor that no matter who is running government, our ultimate allegiance is owed to God. It’s not to family, tribal, national, social, or other Caesar-figures in our lives. Allegiance to God isn’t merely an abstract concept. Allegiance to God includes confronting the ethical implications and doing the work of interacting with rulers and systems of power and holding them accountable.

Remember that allegiance always carries a cost. When Jesus told his interrogators to give Caesar the things that belonged to Caesar and to God the things that belong to God, he pointed them to the thorny issue of cost. It seems there was something akin to a Tea Party movement in his lifetime. Indeed, there seems to always be a view that allegiance (whether to God, government, or anything else) should be cost-free.

Jesus didn’t duck the cost imperative that is a constant factor concerning allegiance. In the final analysis, whether we are truly loyal turns on whether and how much we are willing to sacrifice concerning something or someone. Notice how Jesus turned the question on his interrogators. They asked him “Is is lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” They were talking about an exaction. Jesus answered “Give … to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” Jesus was talking about making an offering!

It is hard to find people of faith who support the idea that taxes represent one of the ways loyal people offer their allegiance. Few sermons are preached that illuminate us to see taxes as offering our money so roads can be paved, schools can be built, people can have access to health care regardless to wealth, air and water can be clean and protected from contamination and contaminators, and the vulnerable among us can be sheltered, protected, and lifted. Many who claim to be followers of Jesus, who answered “Give …,” when it comes to government, appear to have lost our voices if not our minds about the inextricable relationship between allegiance and cost.

I cannot leave my discourse with you without reminding you that we proclaim that God showed his allegiance to us—we call it love—by sending the Son into the world. God offered the Son to the world. It was not an exaction, but an offering, that God gave us. And it was not an exaction, but an offering that Jesus presented at Calvary. At Calvary, Jesus offered Caesar and God what only Jesus could offer—his life. In Jesus, God shows us that allegiance to power always carry a cost.

The issue is whether we view the cost as an exaction or an offering. An exaction is what someone more powerful takes from us, but an offering is what we give using our power to convey or withhold.

- At Calvary, the Roman government thought it was imposing a punishment. In Jesus, God made an offering through the power of love.

- At Calvary, the enemies of Jesus thought they were silencing a popular preacher and ending the challenge of his message about God’s love to their power. But in Jesus, God revealed the power of love that offers itself.

- In Jesus, God offered power in sacrifice.

- In Jesus, God offered power in peace-making despite being surrounded and the instruments of war.

- In Jesus, God offered power without regard to class, privilege, ancestry, social status, or religious standing.

- In Jesus, God offered life to us with the power to confront the Caesars of our time and place no matter what form they take or name is assigned to them.

- And in Jesus, God calls us to be transformed by divine power to offer ourselves as agents of love, joy, peace, generosity, kindness, patience, faithfulness, and justice in a world of Caesars.

In Jesus, God calls us to offer ourselves as agents of divine love who will not shrink to “loaded question” kind of living. God calls us to live as ambassadors of that divine power to the world. Have we heard that call?

If so, let us live it by embracing its implications and fulfilling its duties with every breath and heartbeat. Let us live as people who know that whatever the Caesars of our time and place may claim, the universe and all within in it belong to God, not to any Caesar.

Live, my sisters and brothers, as God’s people. Live as God’s emissaries. Live in God’s redeeming power. Let’s offer ourselves to fulfill God’ wonderful purposes. In obedience to the life and example of Jesus and thru the power of the Holy Spirit, give the Caesars of our time and place what belongs to them, always alert and faithful to fulfill our calling as God’s people.

Then people will not just know Jesus was talking about power. They’ll know we’ve been listening. Amen.

Pastor at New Millennium Church in Little Rock, Arkansas, a retired state court trial judge, a trustee of the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, author of two books and three blogs, a consultant on cultural competency and inclusion, and a contributing correspondent at Good Faith Media.