“If you can’t measure it, then it doesn’t exist.”

This sentiment, or versions of it, is prevalent across a whole range of areas in society and the church.

On the face of it, this makes sense. It seems sensible to plan the amount of food you’re cooking for the number of people you expect at a drop-in.

It seems wise to know how many people you have able to volunteer for your new project and what skills they bring.

It is inconceivable that you would start a new initiative without checking what financial and other costs it might incur. And, of course, how you will measure “success”?

Graih, the charity I work for on the Isle of Man, has been running a pilot night shelter through this year, partly to test the level of need for rough sleepers on the island.

As part of this, we have been collecting basic data and keeping an eye on the numbers of people coming in.

Among our guests we’ve sheltered have been an 88-year-old woman, a young man with little life or communication skills abandoned by all other services and a teenage girl struggling with chaos and sexual exploitation.

It has been used more than we anticipated and we’re in the midst of conversations about how to resource it come January 2020 when the current funding runs out.

Anyone involved with charities and money will know how these conversations run.

How many people have you helped? How have you measured success? How much has it cost? Can it be done cheaper? “Justify yourselves,” say the ones who hold the purse strings.

While there may be elements of wisdom in these conversations, they leave me uncomfortable.

What about grace and generosity and gift? How do we quantify the fact that someone destitute has received basic shelter? What price can be placed upon human dignity and worth?

We live in a society that is bent on the commodification and monetization of every aspect of life.

If it has no financial worth that can be compared, contrasted, weighed, measured and cut, then it has no worth. Free things are suspicious.

It made me think about the deliciously ambiguous stories about David and his census in 2 Samuel 24 and 1 Chronicles 21.

In Samuel, the Lord incites David to take a census of Israel and then punishes Israel for it. In Chronicles, the incitement is Satan’s work and the punishment the same.

It isn’t spelled out why the act of numbering was so bad; David simply laments that he has “done very foolishly” (2 Samuel 24:10).

Surely, it’s wise to know how many people, particularly warriors, you have? It’s sensible stewardship.

Or maybe it’s a poke in the eye of the God of graceful provision, a lack of trust in what is given, a desire to know and manipulate and simply be in control.

In a typically provocative essay discussing the Torah in his book, “Tenacious Solidarity: Biblical Provocations on Race, Religion, Climate and the Economy,” Walter Brueggemann contrasts forgiveness, especially the practical forgiveness of debts so characteristic of God, with the attitude of “bookkeeping” – everything and everyone must be measured, put in their place, debts insisted upon and paid in full.

The covenant leads to grace, generosity, justice, hospitality and the forgiveness of debts; idolatry insists on bookkeeping, charity (understood here as an impersonal and condescending giving of surplus) and parsimony.

The desire to measure and value everything in monetary terms always tends to dehumanization and idolatry.

As people of a gracious God, surely, we know that the most important things in life are free.

We know that life itself is a grace and a gift, and that everything we are and have does not belong to us but to the one who loves us.

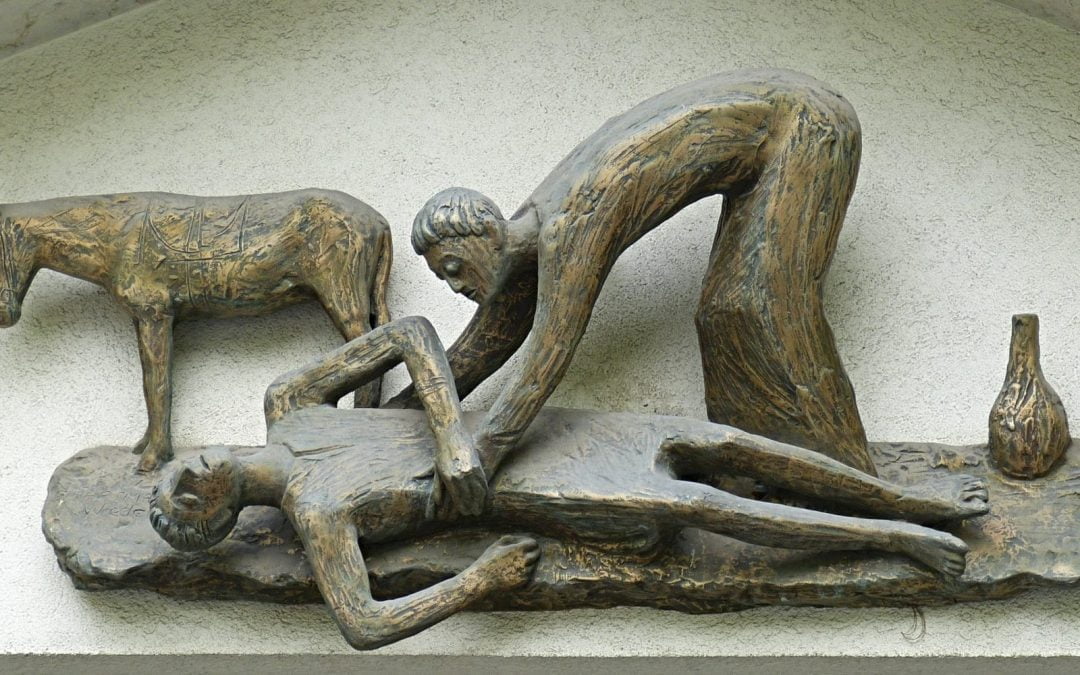

What’s more, we belong to a God scandalously prodigal, a feasting Messiah, one unashamed when anointed with precious perfume and positively reckless when it comes to planning for the future, preferring instead to side with the birds of the field in their dependence on creation.

Ultimately, of course, Jesus didn’t insist on clinging to any rights or power or wealth but gave everything for love (not money).

I listened to a discussion on the radio recently about the profit motive. One person advocated it as the crucial factor and motivation in most human progress.

This baffles me. The things I value most, and I suspect this is true for many people, are not financial. The relationships with those I love, the time spent together as a family, the celebrations we share, the sense of presence and being with others.

Are these things of less worth because they involve no money? Do I want less peace and justice in the world for these precious people because I get no payment for it?

In a culture of commodification and monetization, it becomes even more imperative that the church embodies an alternative vision of human life and human flourishing, rooted in our dependence upon the creator’s gifts. What value is basic shelter for a homeless person?

Well, we belong to a Savior seen most clearly in the poor (Matthew 25). What value would we put on spending time with Jesus? How much money is that worth?

The best things in life are free.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in The Baptist Times, the online newspaper of the Baptist Union of Great Britain. It is used with permission.

Michael Manning is a co-ordinator of Graih, a charity serving those who are homeless and in insecure accommodation on the Isle of Man. He lives with his family in a shared household and belongs to Broadway Baptist Church in Douglas. He is the author of “No King, But God – Walking as Jesus Walked.”