A refrigerator magnet I had years ago said, “If you aren’t going to ordain women, why baptize girls?” Funny – not funny!

Perhaps there is a corollary for theological education. “If churches won’t call women, why should seminaries educate them?”

Indeed, many churches and seminaries in the U.S. and globally would answer that last question, “Right! No need to educate women for vocations that do not belong to them.”

Southern Baptists and Roman Catholics, America’s two largest religious groups, do not call women as pastors or priests and educate significantly more men than women in their seminaries.

For other Protestants in the last century, theological education did become a pathway for women into vocations that both inspired and transformed lives, churches, denominations and the church universal.

In the most recent decades, women’s leadership in the church has grown by leaps and bounds, yet for women, the pace of growth in theological education has slowed significantly.

At the time of the first International Women’s Day in 1911, theological education for women happened informally in local churches or through denominational training events.

The content of that education was largely focused on how to be a proper Christian wife and mother.

Black Baptist women and white Baptist women each supported schools of formal theological education in the first decade of the 20th century; the focus was on single women who wanted to be missionaries.

To be sure, wives and daughters of men studying formally to be pastors and theologians found ways to borrow the education that came to their households. Formal education for women to pastor congregations, however, was nonexistent.

In 1911, women in the U.S. did not have the right to vote or hold office. They rarely graduated from college. And women almost never pastored churches, with some notable exceptions in the Pentecostal traditions.

One hundred and eight years later, the world has changed dramatically for women, including theological education opportunities. Thousands of women each year since the early 1970s receive preparation and training for ministry.

In the past century, theological education for women has shifted from largely church-based, missionary-oriented and domestically focused to become more school-based, ministry-oriented and professionally focused, especially among mainline seminaries.

Vestiges of the early 20th century model of theological education for single missionary women or preparation to be a pastor’s wife do remain, and some evangelical seminaries have reinvigorated such programs. Catholic institutions are no longer training priests exclusively, as they once did.

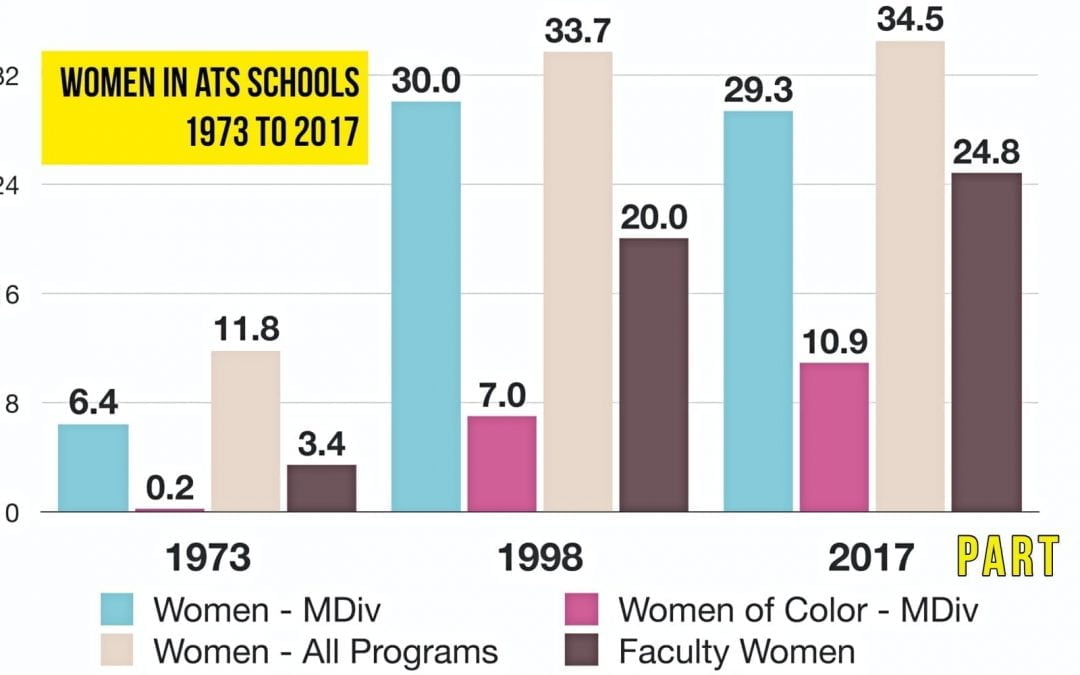

A growing number of lay ecclesial ministers receive masters level training in seminaries and divinity schools, as highlighted in the graphic at the top of this article.

Recently, I published the State of Clergywomen in the U.S., which highlights trends and changes in theological education over the last two decades. Here are eight trends worth noting during this International Women’s Week:

- In 2018, the Association of Theological Schools in the U.S. and Canada (ATS) reported that women make up about 25 percent of the deans and 13 percent of the presidents of theological schools. The numbers have been rising since 1998 but very slowly.

- The number of faculty women in theological education has grown from 20 percent in 1998 to 24.8 percent in 2017, and the greatest increase is with full-time professors.

- The percentage of women overall who are earning the masters of divinity degree, the basic degree for people who want to be pastors, chaplains and so on, has dropped slightly in the last 20 years.

- Since 2008, the modes of delivery of higher education everywhere, and seminaries in particular, are changing rapidly. More education is moving into online formats. Seminaries and divinity schools are under stress, and some are taking on massive realignment and change. For example, some schools are moving, merging or closing.

- Seminary debt for students continues to grow, which may be contributing to lower enrollments since the recession that started in 2008. It is not clear how the impact may be gender-specific, except to say that lesser employment opportunities for women in ministry means the options for paying back student loans are more challenging for women.

- White-identifying women are going to seminary in significantly lower numbers since the recession of 2008.

- Women of color, however, are going to seminary in greater numbers and are making up a greater percentage of the total student enrollment. Yet, women of color are often affiliated with denominations that depend heavily on volunteer labor and pay a lesser number of professional ministers.

- In mainline denominations, women now constitute almost one third of all ordained clergy. Women in mainline Association of Theological Schools have hovered around 50 percent of the students for 20 years. What does the persistent, if slowly closing, gap between seminary training (50 percent) and ordination (32 percent) mean?

These trends and others that you can read about in the State of Clergywomen report paint a somewhat bleak picture for women in theological education in 2019.

Returning to the question “Why should seminaries educate women?” I have lots to say. Look for Part 2 of this assessment tomorrow.

Editor’s note: This is the first of two columns. Part two is available here. This article is part of a series for International Women’s Day (March 8). The previous articles in the series are:

Why You Need to Say the Other F Word in Church by Meredith Stone

Allowing Sexual Abuse Survivors to Find Their Voice by Pam Durso

She Matters: Providing Hope, Opportunity to Women Globally by Jennifer Lau

Eileen Campbell-Reed teaches at Central Seminary, and she is codirector of the Learning Pastoral Imagination Project. In October 2018 she published the State of Clergywomen in the U.S., and she hosts Three Minute Ministry Mentor.