Over the 33 years since the first national observance of the birth of Martin Luther King Jr., the controversial holiday has become a process of selective memory.

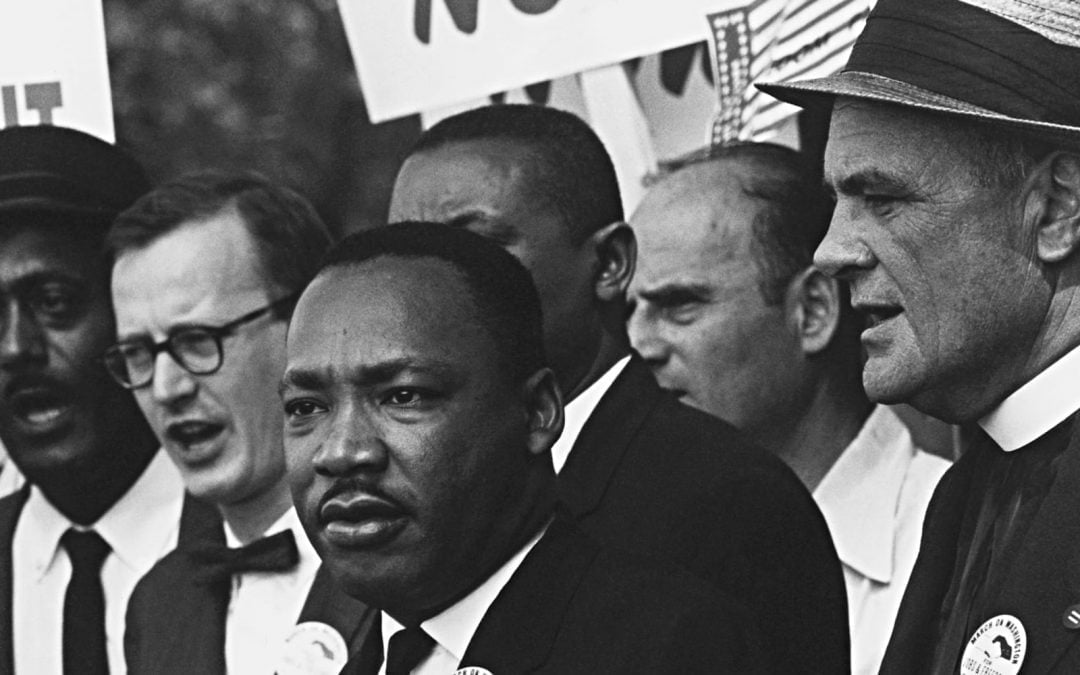

Year by year, the day has become an echo chamber for the last few minutes of the iconic speech, delivered in the shadows of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 28, 1963, at the culmination of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Read the speech or, better, watch and listen to an unedited video.

Although the speech ends on a high note of hope, only the last one-third of the address could be described as a composition in a major key.

The first two-thirds of the speech have the character of a dirge, a composition in a minor key.

Only at the end do readers and listeners swell with the power of the repetitions of “I have a dream!” and “Let freedom ring.”

The structure of the speech appears to follow the pattern of the prophet Amos, who is responsible for one of King’s signature phrases: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteous a never-ending stream” (Amos 5:24).

Amos was not irenic. His hopes for justice and righteousness drove him to deliver a dirge – a composition in a minor key – that issued condemnations of Israel’s neighbors and, then, directed to Israel.

Only after every nation of the region, with Israel receiving the brunt of the prophetic ire, was called out did Amos allow himself the freedom to dream of the restoration of Israel. “In that day, … declares the Lord,” restoration will come (Amos 9:11-12).

And, then, “The days are coming … when the reaper will be overtaken by the plowman, and the planter by the one treading grapes. New wine will drip from the mountains and flow from all the hills, and I [the Lord] will bring my people Israel back from exile (Amos 9:13-14).

In the second paragraph of King’s speech, he declared that those who joined the March on Washington came “to our nation’s capital to cash a check,” noting that “the architects of our republic … were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir [when they expressed the conviction that] all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

He continued, “It is obvious … that America has defaulted on this promissory note. … America has given the Negro people a bad check, which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

Dirge, indeed.

To eyes and ears in 2019, King’s repeated references to “the Negro” may appear either quaint, anachronistic or not politically correct. There are at least 15 Negro references. Even in King’s day, there were significant pushbacks against the word.

In the same years King was promoting a nonviolent civil disobedience to institutional racism and oppression, others demanded social, civil and political transformation.

As the civil rights movement was aborning, King struggled with the presence and influence of Malcom X and, later, Stokely Carmichael and the Black Power Movement.

Over the next five years, however, King moved closer to Malcom’s stridency and the Black Power urgent demands for change.

Another example of the dirge quality of the 1963 speech is King’s stark documentation of voter suppression, found in the lines: “We can never be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.”

In our day, #BlackLivesMatter, the widespread resistance to voter-ID legislation and racially motivated gerrymandering remind us that King’s nightmare continues to evoke righteous indignation and, too, increased motivation to promote King’s dream without muting the reality of the nightmare.

Finally, King’s speech helps us focus upon another insidious characteristic of our nation’s failure to address racial injustice.

Early in the speech, King resists “the tranquilizing drug of gradualism” and a demand for “cooling off” amid heightened social attention to racial injustice.

The fact is that in the 1960s and beyond, prominent white politicians, social activists and theologians – all of whom claimed to be interested in justice and righteousness – dragged their moral feet when faced with the reality of systemic racism.

King was prescient.

The paternalisms of so-called sneaky white liberals continues to impede our progress toward the realization of King’s dream.

We continue to live in a nightmare. We continue to hope for the dream.

Editor’s note: This article is part of a series for MLK Day 2019. The previous article in the series is:

King’s Perennial Question: Do We Pursue Chaos or Community? by Colin Harris