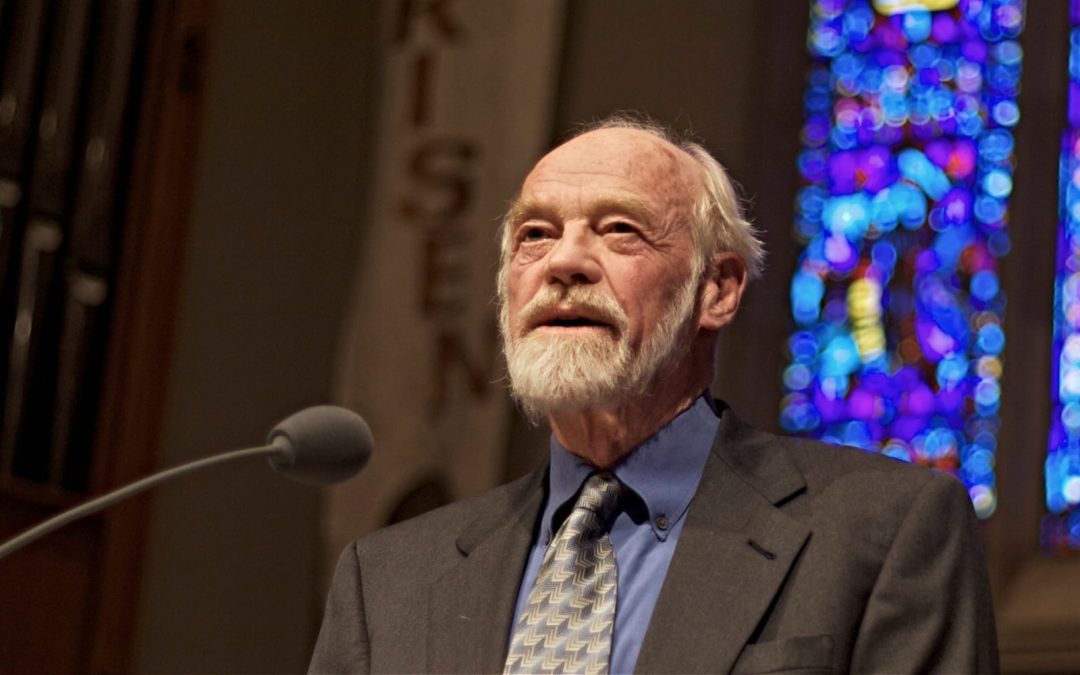

The news on Monday that Eugene Peterson had died will be greeted by thousands of pastors with a mixture of reactive sadness that his life has ended, but also with enduring gratitude that it was lived the way he lived it.

Eugene Peterson was a pastor, never anything else.

In the second half of his life, he became a teacher of spirituality at one of the premier evangelical seminaries in North America, but the person who became a professor was, first and foremost, a pastor.

His professorship was merely the medium through which he continued to be a pastor and spiritual guide to hundreds of students and thousands of pastors.

I met Peterson only once. It’s worth telling the story.

I was booked to go to the Conference at St. Ninians in Crieff in central Scotland in September 1997. I had to cancel due to the sudden death of my mother-in-law.

The day after the funeral, which was also the day after the conference finished, I phoned St. Ninians and asked if Peterson was still there.

He was, and when he heard I was willing to divert to come through Crieff just to meet him, he rearranged his timetable and asked if I could be in Crieff by 11 a.m. for coffee. Yes, I could, and yes, I did.

I wanted to thank him for his books and for the way they had reshaped my thinking, realigned my heart and reconfirmed that the calling of a pastor is fulfilled by faithfulness and pursued in disciplined love for Christ and his church.

A long obedience in the same direction; working the angles; being a contemplative pastor; choosing five smooth stones for pastoral work; answering God – what I mean is these and other titles of his books rang with a clear pastoral intent. If I had to choose which of his books have meant most, I’d be hard-pushed.

It was a sunny cold day, so we sat on the bench in front of St. Ninians and talked theology, pastoral care and spirituality.

His appreciation of my own book on evangelical spirituality was one of my more humbling moments, and I suspect his way of deflecting my admiration and indebtedness to his own writing ministry.

Because among the most obvious characteristics of this man was his self-deprecation, not in false modesty, but in genuine gospel humility.

We spent an hour or so, we prayed together, and he commended our family as we sorrowed in bereavement, we shook hands and parted.

But not before he went into the St. Ninian’s bookstore, bought one of his own books and inscribed it as a memento of our conversation.

It’s one of those moments, and one of those gifts, that has taken on increasing significance over the years.

Now reading it and remembering Peterson is a sacramental act, bringing back so much of the sense and sensitivity of someone who embodied so much of what over the years I have aimed at. So that is my personal debt.

But many others knew him better and met him more often, and they are the more blessed for it. But among his most important gifts were the books he wrote.

Once he began to teach on spirituality and on pastoral care in Vancouver, many of the themes that enriched and expanded our understanding of ministry began to recur, so that his later work tended to be derivative from his earlier work.

That isn’t a criticism so much as a recognition that certain key principles and stated priorities would always find their way into whatever he wrote on pastoral care, prayer, preaching, spiritual direction and pastoral counsel.

His writing and his thought, indeed his way of thinking, was thoroughly biblical, drenched in Scripture and mixed with wider reading across the classics of literature, theology and biblical studies.

He was a poet and a lover of poetry. He lived in the Psalms and quarried in the Prophets, walked in the Gospel stories and cultivated those occasionally tetchy and pastorally oriented letters of Paul.

And out of all this, Peterson wrote about the ministry, the pastoral life, the ways of prayer, the psychology and spirituality of Christian experience, and he did so as one who knew he was as fallible, vulnerable and in need of grace as the rest of us who read his words.

But read them we did. And ministers who were bruised, disillusioned, exhausted, wounded, bored, anxious, defensive or confused were helped to get things in proportion, to see all the downsides in the light of eternity and to recover a hopefulness that depended not on their skill, technique or eagerness to fulfil expectations, but on the gospel of a grace that overwhelms, a wisdom that seems foolish and a love that undergirds and underwrites every instance of ministry offered in weakness.

And alongside the reorientations and return to true vocation, Peterson taught the disciplines that sustain ministry, that cultivate the soul to a fertile tilth and a suitable depth to contain and nurture more of the eternal love of God in Christ.

Bible reading and long pondering of the text aiming at a familiarity of habit to know the text. But not as cognitive control or academic curiosity, more as a pharmacist knows medicine, or a fly-fisher knows the flies, the river and the light, or a driver knows a road that is familiar but still, not to be treated with familiar complacency.

Such reading presupposed long and persevering prayer and the cultivated trustfulness in the ministry of the Holy Spirit who takes of the things of Jesus and brings them to remembrance, leads us to deeper apprehension of truth and equips us with gifts we never knew we had.

If I were to choose one book from the plethora of options, I couldn’t.

Yes, I think “Reversed Thunder” the finest writing he ever did tied to a biblical text. But what about “Five Smooth Stones for Pastoral Work” and “Working the Angles” as fundamental texts of any pastoral theology presupposing a Christ-centered spirituality?

His longest series of volumes on a spiritual theology are his most recent, and probably now his best known because they were most recently in print.

But they gather so much from those earlier books wrought out in the workshop of being a pastor in the community of Christ the King.

And these earlier books I treasure because they have the footprints of my pastoral journeying all over them.

Peterson never sought fame or the accolades of grateful readers. But in evangelical circles his work is well known; he is a trusted resource among ministers.

The vision of ministry he commended and enacted, and out of which came so much of his best and most durable writing, is now in turn enacted and incarnated in the many whom he taught through his writings and in Regent’s College in Vancouver.

For myself, I owe deep, unpayable debts to this man.

Not that he ever sought or wanted to be seen as a planet around which acolytes orbit; in faithfulness to his own teaching what he would want more than anything else is for ministers to minister out of those deep places of contemplative prayer and faithful study and passion-fueled vocation, nourished by Bible, community and the intimacy and majesty of prayer.

From early on in my ministry, I have been privileged to have encountered a mind and a ministry that does something very hard to do – makes you want to keep on being a pastor, a servant of Christ and of the Body of Christ.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared on Gordon’s blog, Living Wittily. It is used with permission.

Part-time minister of Montrose Baptist Church in Angus, Scotland, and the former principal of the Scottish Baptist College. He is on the advisory board of the Centre for Ministry Studies, University of Aberdeen, and is honorary lecturer in the School of Divinity, History and Philosophy.