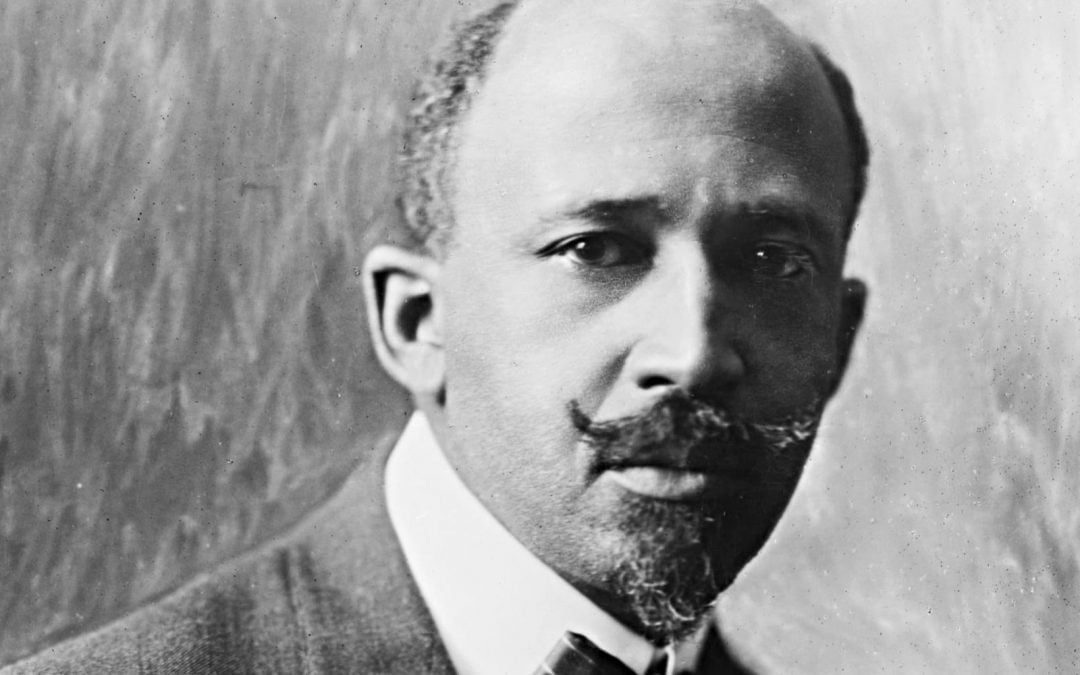

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, born 150 years ago in February 1868, was the great-grandson of James Du Bois, a white plantation owner in the Bahamas.

However, W.E.B. pronounced his name “doo-boyz” rather than with the French pronunciation.

When he was only 20, Du Bois graduated from Fisk University. He went on to study at Harvard, at the University of Berlin and then in 1895 became the first African-American to be awarded a Ph.D. degree by Harvard.

In 1903, Du Bois published his seminal work, “The Souls of Black Folk,” a collection of 14 essays – and now, 115 years later, it is still in print and relevant.

One central point made on the book’s very first page seems, unfortunately, still to be true: “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” This statement is an accurate assessment of the 21st century as well.

In that book, and consistently through the following years, Du Bois adamantly opposed the idea of biological white superiority.

Partly for that reason, in 1909 he co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and long served as editor of its monthly magazine, “The Crisis.”

Du Bois taught at Atlanta University from 1897 to 1910, and then, at the age of 66, he went back to that school and was chair of the department of sociology from 1934 to 1944.

During most of the 1950s, Du Bois was unable to travel outside the U.S. because of his alleged ties with Communist nations.

In 1961, Du Bois moved to Ghana – and later became a citizen of that country, where he died in 1963 at the age of 95.

Although they were the two most important African-American leaders after Frederick Douglass, who died in 1895, an ongoing controversy existed between Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, who was 12 years his senior.

Du Bois’ criticism of Washington was eloquently voiced in the third essay in “The Souls of Black Folk” – and it lasted until Washington’s death in 1915.

In what Du Bois called the “Atlanta Compromise,” Washington seemed to accept the view that blacks were inferior to whites.

Du Bois, however, strenuously objected to that idea and called for full equality of blacks and whites.

He wanted complete rejection of all Jim Crow laws and ways of thinking. He favored confrontation rather than compromise in seeking to erase the problematic color line.

Through the years, I never heard as much, or learned as much, about Du Bois as about other noted black leaders, such as Douglass or Washington.

Maybe, that was partly because Du Bois leaned toward socialism, was prosecuted as a Red sympathizer in the 1950s and did join the Communist Party in 1961.

Nevertheless, I have been deeply impressed by my recent reading of and about Du Bois, and I close with words spoken by Martin Luther King Jr. (and which can be read here) on the 100th anniversary of Du Bois’ birth.

King declared that Du Bois was “one of the most remarkable men of our time,” a scholar who “recognized that the keystone in the arch of oppression [of blacks] was the myth of inferiority” and who “dedicated his brilliant talents to demolish” that myth.

Du Bois’ legacy lives on – and his voice still needs to be heard today.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared on Seat’s blog, The View from this Seat. It is used with permission.

A missionary to Japan from 1966-2004, he is both professor emeritus of Seinan Gakuin University and pastor emeritus of Fukuoka International Church.